Late Antiquity and the Paleosciences: New Frontiers

By Kristina Sessa, Coeditor of Studies in Late Antiquity and Coeditor, with Guest Editor Timothy P. Newfield, of SLA's special issue, "Paleoscience and the Study of Late Antiquity"

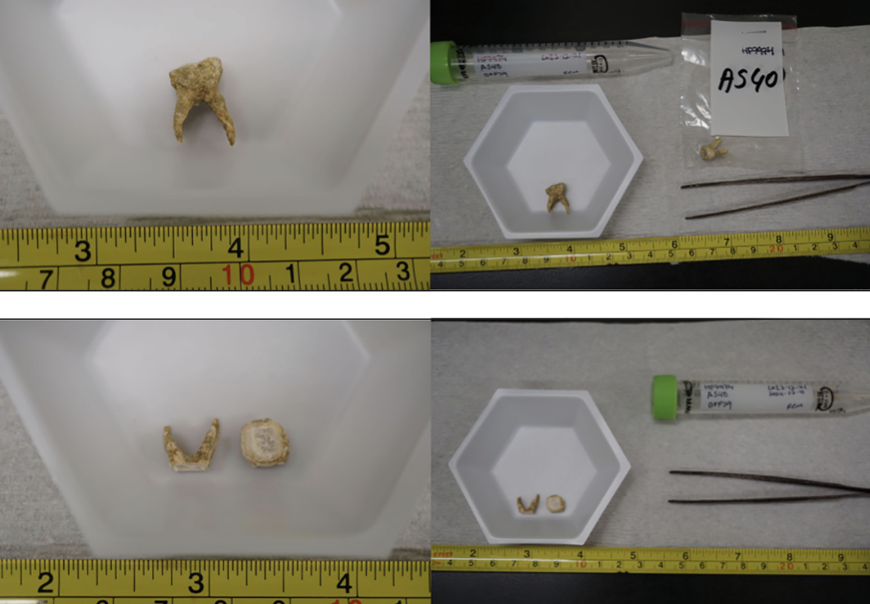

Over the past decade, historians of Late Antiquity, long dependent on traditional tools of textual interpretation and archaeological methods and data, are increasingly turning to an unexpected partner: the natural sciences. Pollen grains buried in lake mud now tell us how people reshaped landscapes. Tree rings provide evidence of forgotten droughts. Genomes, recovered from human bones and teeth, shed light on migrations, family ties, and deadly pathogens like Yersinia pestis, the bacterium behind the Justinianic Plague. In fact, Studies in Late Antiquity's new special issue, "Paleoscience and the Study of Late Antiquity" presents the first genetically-based evidence of plague from outside sixth-century Constantinople—a region that late ancient texts have long claimed was especially hard hit by the disease but until now offered no scientific confirmation. What was once the domain of archaeologists alone has expanded into an interdisciplinary frontier where geneticists, climate scientists, ecologists and historians work together to tackle questions none could solve on their own.

Yet this new, collaborative era of research brings its own challenges, misunderstandings, and heated debates. Historians stepping into science-forward research often face steep learning curves: unfamiliar jargon, statistical modeling, and proxy-based data that can feel more like magic than method. After all, how does degraded DNA from a sixth-century tooth become a genome? Misunderstanding these processes isn’t just awkward; it can lead to overconfident claims, flawed interpretations, and friction between disciplines. At the same time, scientists are often equally uncomfortable with the challenges posed by textual sources—despite the fact that many present their research as part of familiar grand narratives without fully recognizing the limits of these constructions. What is more, scientists themselves emphasize that their data are not the unchanging bedrock humanists often assume. Proxies shift, archives expand, and methods evolve. Historians must keep up and they must recognize their science-infused histories will continue to evolve.

While no single set of articles can possibly resolve these problems, in particular the need to bridge disciplinary expertise and the deep, methodological differences still in place between modern scientific and humanistic study, this special issue of SLA seeks to accelerate existing conversations and begin new ones. Here, we bring together a highly diverse and distinguished group of paleoscientists, archaeologists, and environmental historians not simply to summarize their findings but to lay out in clear and candid terms the possibilities as well as limitations of their research for historical interpretation.

To capture the dynamism of these debates and to give scholars space to articulate their methods clearly and concisely, the special issue integrates several different formats, which are organized into four sections. Ultimately, this issue is a call for deeper collaboration built on humility, curiosity, and mutual respect. Historians must learn enough science to avoid misinterpretation; scientists must recognize the interpretive nuance that historians bring to the study of the past.

Dialogues on Paleogenetics

Presented first are two lively, annotated podcast-to-print conversations that bring together geneticists, evolutionary biologists, archaeologists, and historians.

- The human paleogenetics discussion explores how DNA reshapes stories of migration, kinship, and identity, while tackling the highly sensitive question of whether genetics can (or should) be used to discuss ethnicity.

- The pathogen paleogenetics dialogue dives into how scientists reconstruct ancient genomes, including Y. pestis, and what these findings do, and don’t, tell us about historical disease.

Both conversations highlight a recurring theme: Breakthroughs happen only when disciplines work together, and failure often happens precisely when researchers disregard the epistemological frameworks of other disciplines.

Case Studies: Bones, Plague, and the Promise of Bioarchaeology

The second section offers concrete examples of interdisciplinary research in action. Both essays also directly confront ethical questions about destructive sampling of human remains and the hard history of bioarchaeology as a discipline.

- “Grave Lessons” explores what human skeletons reveal about migration, disease, diet, and stress, and where their interpretive power ends.

- “Discovery and Dilemma” announces a major finding: the first identification of Y. pestis from sixth-century Constantinople. Yet the authors also reveal the frustration of scientific limitations—despite detecting the pathogen, they couldn’t yet recover a full genome, thereby limiting historical interpretation—and articulate some of the burdens paleogenetic work can entail.

Critical Commentary: Methods Under the Microscope

Next come reflections by historians who interrogate not just the data, but the assumptions behind the data:

- How do we teach paleoscience to undergraduate history students?

- Why are earthquake catalogs deceptively unreliable?

- What goes wrong and what do we miss when we diagnose diseases across centuries?

- How should we think about causation when climate and environment enter the historical narrative?

These essays remind readers that methods shape conclusions, and flawed methods lead to flawed history.

Global Perspectives: When Interdisciplinarity Changes Entire Fields

The final section, composed of review essays on recent books, zooms out to look at other regions and premodern periods where scientists and humanists have already truly transformed our understanding of the premodern world:

- The steppe empires of Central Asia

- The Khmer Empire around Angkor Wat

- Medieval Norse Greenland

- The Second Plague Pandemic

These reviews help to expand our understanding of paleoscience in regions outside the more familiar Mediterranean frame of Late Antiquity, and to reveal how collaborative science-forward history has reshaped premodern history worldwide.

We invite you to read Studies in Late Antiquity's special issue, "Paleoscience and the Study of Late Antiquity," for free online for a limited time.

POD copies of the special issue (issue 9.4), as well as other individual issues of SLA, can be purchased on the journal’s site.

For ongoing access to Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, please ask your librarian to subscribe and/or purchase an individual subscription.