Mapping Lesbian History: Q&A with Cameron Blevins and Annelise Heinz

Much of the scholarship of queer history, as well as the places that loom largest in the public conversation—such as Manhattan’s Stonewall Inn, or San Francisco’s Castro district and Miami’s beaches—tend to focus on gay men and urban spaces. A fuller history is revealed by historians Cameron Blevins and Annelise Heinz, who use digital mapping technology to uncover a hidden geography of lesbian life in the 1970s and 1980s. Through mapping thousands of locations mentioned in a lesbian feminist periodical, the authors trace patterns of connection among lesbian women in urban areas, small towns, and rural America.

Their article in Pacific Historical Review, “Separated, but far from alone”: Forging Lesbian Networks in the 1970s-1980s,” received the Louis Knott Koontz Memorial Award of the Pacific Coast Branch-American Historical Association, the Barbara “Penny” Kanner Award of the Western Association of Women Historians, and the Article Prize of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians for best article in the fields of the history of women, gender, and/or sexuality.

Tell us about your article.

Annelise: Our article examines how women forged both in-person and long-distance networks in the 1970s and 1980s through the pages of the bi-monthly publication Lesbian Connection, The article focuses on three main types of connection built through the magazine: First, overcoming isolation—showing how lesbian women living in rural areas and small towns, many of them totally closeted, were learning about lesbian life and community through the magazine. Second: economic networks and commercial exchange that developed through advertisements and annual catalogs. And third, exploring travel and mobility through the publication’s unique "Contact Dyke Directory"—a listing of volunteers who served as local points of contact for fellow lesbians traveling to or moving to their area.

Your research focused on an underground magazine, Lesbian Connection. Tell us why you chose this particular historical source.

Annelise: Lesbian Connection was (and probably still is) the most widely circulated lesbian and lesbian feminist periodical, distributed globally but primarily in North America. It's always been "free to all lesbians"—you pay more if you can, less if you can't. It also relies on readers themselves to submit much of its content—articles, letters, advertisements, classified ads, announcements—giving it a kind of “open mic” quality or like the bulletin board at a local coffeeshop. One reader described it as “like having an ongoing dialogue with several hundred witty, articulate, womyn-loving womyn.” All of this made the periodical an invaluable source for recovering lesbian voices and experiences during this period—although it’s important to note that the magazine certainly wasn’t representative of all lesbians given its largely white readership.

Your article is full of maps—how do the maps give us extra insight into this history?

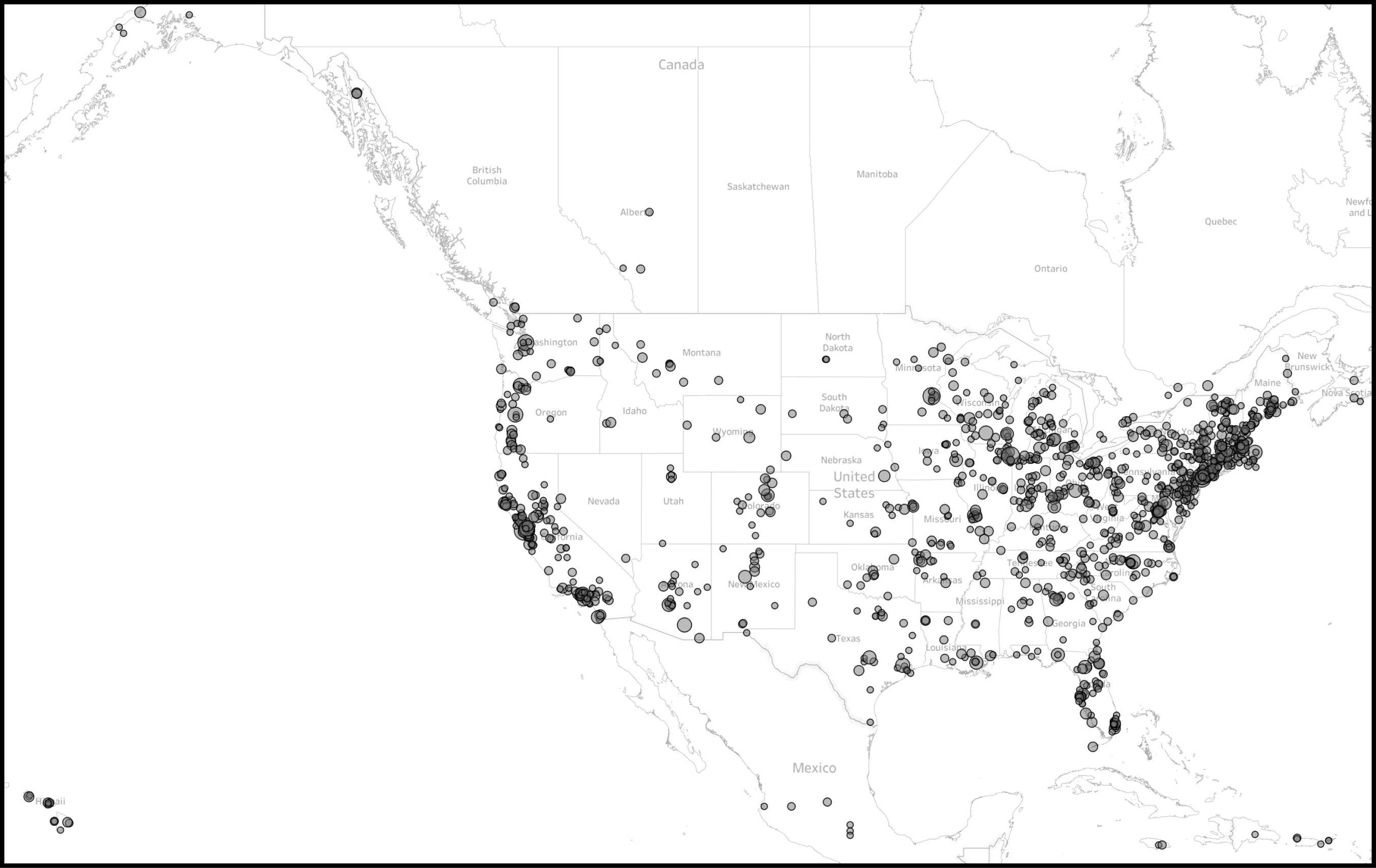

Cameron: We realized fairly quickly that Lesbian Connection was packed full of really rich and detailed geographic information. All of this reader-submitted content coming in was typically anchored to a specific place (like an advertisement for a candle store in Unicoi, Tennessee). We chose a sample of 26 issues from 1975 to 1989 and, working with research assistants, transcribed around 5,100 instances of specific towns, cities, etc. that appeared in these issues.

When you put all these different places onto a map, you can start to see clusters and patterns that you wouldn’t pick up on just reading through the magazine yourself. Take the tiny town of Mendocino, located on the northern California coast—it showed up as a surprisingly big cluster on our maps. When we looked closer, we realized it was a lesbian resort destination with bed-and-breakfasts and travel services. You'd never pick up on that pattern just reading individual issues, but when you map everything, suddenly you see these types of clusters and can ask: "What's going on there?"

How does your article change the way we think about lesbian history?

Cameron: This mapping approach helped us uncover some pretty surprising patterns. A lot of queer history and scholarship has focused on big urban cities like New York City or San Francisco. But if you look at our maps you see many, many more places. You get hundreds of tiny rural places like Pine River, Wisconsin, or Colby, Kansas. At the same time, mid-sized and smaller cities like Gainesville, Florida or Fort Wayne, Indiana were showing up at a similar rate as much bigger cities like Chicago or Philadelphia.

Annelise: It's hard to overstate how little we know about lesbian history, especially the geography of lesbian communities and networks. Even a word like "gayborhood," which has become a kind of stand-in for where queer people live, is really referring to where gay men live. Our research highlights communities that have been overlooked—folks in rural areas and smaller cities who would especially need the kind of long-distance community that Lesbian Connection provided. We revealed a much more dispersed network that stretched far beyond the country’s big urban centers.

This is a co-authored article, which remains fairly uncommon for historians. How did you start working together and what has that experience been like?

Cameron: Annelise and I originally became friends when we were in graduate school together. Fast-forward to 2021, we’d both just published our first books and were starting to turn towards new research. Annelise reached out to me to ask some questions about mapping . . .

Annelise: I believe I asked, “Can you tell me whether I need to learn GIS or not?”

Cameron: Now, I don’t have a background in queer history, but I do have expertise in digital history and spatial history. I was so intrigued by this project that I basically said, “Hey, why don’t we just work together on this?” Annelise had the subject matter expertise and I took the lead on the spatial analysis, and over many, many, many Zoom meetings we worked together to interpret what we were finding and ultimately write it up into this article.

Annelise: This was my first real collaborative project, and it's been incredibly positive. It’s safe to say that neither of us could have ever written this article on our own. The end product was so much stronger because we each brought something different to the table and it really became greater than the sum of its parts--not just adding A and B together, but actually creating something more meaningful through the process of collaboration.

We invite you to read “Separated, but far from alone”: Forging Lesbian Networks in the 1970s-1980s,” coauthored by Cameron Blevins and Annelise Heinz, for free online for a limited time.

Print copies of the Summer 2024 issue of Pacific Historical Review (issue 93.3), in which the article appears, as well as other individual issues of PHR, can be purchased on the journal’s site.

For ongoing access to PHR, please ask your librarian to subscribe and/or purchase an individual subscription.

We publish PHR in partnership with the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association.