Towards a Humbler, Braver and Kinder Science

By Fernando Racimo, author of Science in Resistance: The Scientist Rebellion for Climate Justice

Science has often been equated with progress—a way of learning about the universe and developing tools to modify it for the betterment of humanity. It has been likened to a “candle in the dark” or even a “universal good.”

In 2025, these metaphors seem rather vacuous. It’s not just that many scholarly fields are on the retreat, thanks to financial cuts to almost everything, from climate science and conservation biology to the many social sciences that are critical to business-as-usual. It’s also that “science” today is anything but a universal good. For many, it is synonymous with violence and oppression. Scientific research powers the war planes and remote-controlled drones dropping death in occupied Palestine; the mass AI-powered surveillance systems deployed in the US, Russia and China; the mega-mining projects destroying entire ecosystems and towns in Germany, Chile, Congo and Zimbabwe. All these would not be possible without armies of technically-trained experts, without massive amounts of scientific knowledge and without the latest state-of-the-art technologies, in large part developed within the walls of the ivory tower.

Is there salvation for science in the 21st century? Can scientists become more than passive subjects of neoliberal dismantlement, or complicit participants in extractivist fascism?

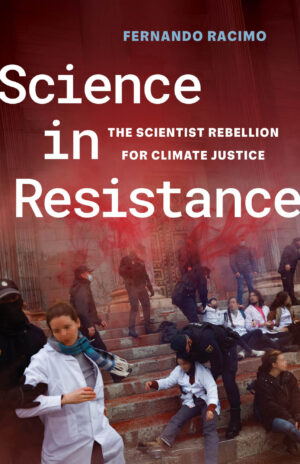

In my new book Science in Resistance: the Scientist Rebellion for Climate Justice, I chart a way forward for the scientific community to face the challenges of a collapsing world—for scientists to confront climate and ecological breakdown, as well as high-tech authoritarianism. In the book, I interviewed 24 scientists who are participating in civil resistance and direct action. They are risking their careers, and sometimes their lives, by defying their places of work, and joining struggles for climate, ecological and social justice. They are all members of the global movement Scientist Rebellion (SR). These “scientist-activists” refuse to resign themselves to passivity or complicity. Instead, they believe that a better science is possible, but only if we dare to break with the chains of the systems that oppress us—with capitalism, with colonialism, and ultimately with “science as usual.”

Since the movement’s origins in 2020, members of SR—among whom I count myself—have blocked roads, disrupted corporate and academic conferences, covered private jets and yachts with paint, occupied luxury car pavilions, and even chained themselves to the White House fence. Some of the scientists I interviewed have spent months in jail. One of SR’s founders, for example, is also a member of the movement Palestine Action, recently proscribed in the UK. In 2021, he was arrested for peacefully disrupting the production of components at an Israeli weapons factory, and sentenced to over two years in prison.

Is there salvation for science in the 21st century? Can scientists become more than passive subjects of neoliberal dismantlement, or complicit participants in extractivist fascism?

Beyond the public faces of the movement, there are also large teams of academics working anonymously behind the frontlines. They are aiding with internal coordination, media framing and logistics. Across the world, these underground academic networks are using decentralized forms of organizing in coordination with student collectives, Indigenous groups and worker movements. Together, they are helping to disrupt both the sites of extraction of fossil fuels and rare earth minerals, as well as the corporate headquarters and state institutions that make this extraction possible.

Scientist-activism is not new. Academics have often participated in progressive struggles, like the university uprisings under apartheid South Africa, or the civil rights movement in North America, where the “teach-in” first gained prominence as a tool for simultaneous disruption and learning. The current wave of activism has borrowed tactics and strategies from these earlier movements, deploying them with a focus on climate justice and global solidarity. This wave is also helping cement the idea that scientists should participate in activism. In other words, there’s a growing awareness that scientific activities can never be neutral, that calls for scientists to stay in the ivory tower are essentially calls to acquiesce to the status quo. And as one scientist-activist I interviewed puts it: “the status quo right now is a deadly state of being.”

As they join these struggles, scientists are also learning lessons in humility. They are realizing that academic expertise is rather limited when it comes to mobilizing for change. Often, the most useful knowledge is the stuff they don’t teach you at school. Instead, scientist-activists are turning to local and Indigenous communities, who have many more years of experience in resistance to state and corporate intrusion. They are also learning that the overly technical and detached way in which they’ve been trained to work can be a disadvantage. When it comes to transformational change, hearts and hands are just as important as minds. As they learn these lessons, scientist-activists are bringing them back to their places of work, trying to transform academic institutions, to make them fit for a rapidly warming planet.

Ultimately, in my book I show how many scientists have come to realize that making polite requests to those in power is no longer a viable option (if it ever was). Scientists-turned-activists are instead rising up in resistance, joining efforts with anti-capitalist and anti-colonial movements around the world. And as they do so, they are also helping to turn science itself into a kinder, humbler and braver endeavor: a science that might, perhaps, help us weather the coming storms.