How to Get Your Quiet Students to Speak Up

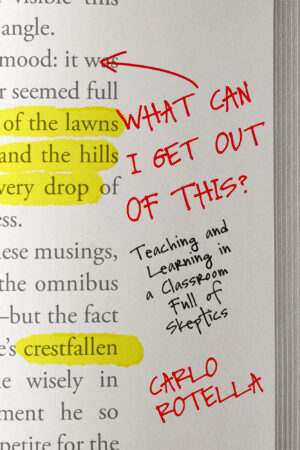

By Carlo Rotella, author of What Can I Get Out of This?: Teaching and Learning in a Classroom Full of Skeptics

Silent students may all seem alike to a frustrated teacher—What’s with college kids these days?—but each student’s silence has a particular provenance and texture, a substrate of lived experience and academic history and inner life. All this backstory goes into creating a problem that we can address with some fairly straightforward solutions straight out of the behavioral psychology textbook: lower the bar to speaking in class by setting up the moment in advance; gently reinforce it when it happens; and if the problem’s really bad, you can even rehearse and reinforce class participation with the student one-on-one in office hours. Becoming aware of this simple truth opens up possibilities for turning silence into speaking up and the greater engagement and fulfillment that comes with it. And that makes a class better for everyone in the room.

My new book What Can I Get Out of This? tells the story of one semester in a required freshman literature course. One principal theme is the importance of citizenship in the community of inquiry we try to build and sustain for the fifteen weeks of the semester. I expect students to ante up and participate in our community by contributing to class discussions. My rule is that we have to hear from everybody at least once every time we meet. My interviews with students made clear that this requirement does lead them to do the reading more often, though it also makes them anxious.

In one chapter, I do a deep dive into the experiences of two students who had things to say but were so paralyzed by fear that they couldn’t raise their hands. They came from very different backgrounds—Kathi came from money and attended a fancy prep school, while Colleen was a first-generation college student from a working-class family—but their difficulties were similar. Colleen said, “I just get in my head too much, and I’ll be practicing what I want to say, if I have an idea, but then I’m just worried that it will sound like not knowing what I’m talking about or the wrong thing.” Kathi said, “I was this, like, anxious little ball—scared of doing, like, one wrong thing.”

I followed the same sequence with both of them. First, I wrote an email to the student reminding her of the class policy of consistent class participation, then I met with her in my office to talk about her difficulty with speaking up and make a plan of action. At these meetings I told her what my first question would be at our next class meeting, which would allow her to prepare an answer in advance. She would put up her hand, and I would call on her right away. Going first would prevent her from building up disabling dread as the class meeting went on. It would also eliminate any need to worry about being preempted by someone else or fitting her comment into the flow of discussion. I asked each to think about whether she wanted to move to the back of the classroom so that others wouldn't see her, or to the front so that she couldn't see others. And we could also rehearse our whole exchange a few times right there in my office: I call on you, you raise your hand and give the answer, I respond positively to reinforce the behavior.

Both Colleen and Kathi managed to establish a habit of speaking up in class by following this jump-start sequence. Overcoming such an aversion can be life-altering. Colleen, in particular, found that when she pushed herself to do this one thing, she found it easier to push herself to talk in other classes, and in other social situations. “Looking back now, I think I’ve grown in every way, like academically, socially, even emotionally," she told me. "In my own friendships sometimes I struggle with being quiet. So now I try to say, Okay, well, maybe I’ll just start the conversation and then the other person will keep going. And instead of being like Oh, I have nothing to say, well, at least I’ll get them talking. It’s like participating at the beginning of class, so then you know that you can participate later as well.” The stakes were especially high for Colleen, who wanted to be an elementary school teacher for as long as she could remember. She believed that school is where people equip themselves to move up and make good in the world, and she wanted to help kids do that. Speaking up wasn’t just expected in my class, and it wasn’t just part of how a student does well in college: it’s what teachers do.

The genuine satisfaction I feel about the quiet triumphs of Colleen and Kathi in my class is tempered by the realization that I let them go too long before intervening and by the even more sobering realization that over the years, I haven’t made the minimal effort to reach other students in their situation. I don’t have that many students, and the effort required of me really is minimal: ten seconds to dash off a not particularly kindly email, twenty minutes of somewhat more gentle conversation in office hours, a scrawled reminder to myself on my class notes to keep an eye out for Kathi’s or Colleen’s hand, a little extra reinforcing emphasis added to my response to whatever they said. Colleen and Kathi had to make a manyfold greater effort to take what felt to them like a big step, and the payoff was significant and enduring.