A Tomato-y Egyptian Lentil Soup for Cooler Days

By Anny Gaul, author of Nile Nightshade: An Egyptian Culinary History of the Tomato

People often ask me how I got from a dissertation about kitchens and cookbooks to a book about tomatoes. I usually answer that I started with my doctoral research and “turned up the tomato.” (I’m not sure anyone finds this turn of phrase as amusing as I do, but it is a fairly accurate description of the process. And not a bad approach to life.)

To mark the occasion, and in a similar move, I’m revisiting a recipe from a classic Egyptian cookbook that I wrote about back in 2020—with an eye to the role of the tomato. This recipe is perfect for fall soup season and offers a preview of key themes in my new book, Nile Nightshade.

In Nile Nightshade, I shows how Egyptians' embrace of the tomato and the emergence of Egypt's modern national identity were both driven by the modernization of the country's food system. Drawing from cookbooks, archival materials, oral histories, and vernacular culture, I follow this commonplace food into the realms of domestic policy and labor through the hands of Egypt's overwhelmingly female home cooks. As they wrote recipes and cooked meals, these women forged key aspects of public culture that defined how Egyptians recognized themselves and one another as Egyptian.

Baladi Lentil Soup

حساء عدس بلدي

Recipe adapted from Usul al-tahi: al-nazari wa-l-ʿamali (Fundamentals of Cooking: Theory and Practice), aka Kitab Abla Nazira, by Nazira Nicola and Bahia Osman (1941), with additional elements based on oral history interviews

Ingredients:

2 cups red or yellow lentils

1 teaspoon of salt, plus more to finish

1 medium-sized red onion, chopped

1 medium-sized carrot, chopped

2 tablespoons of butter, divided

1 large tomato, quartered

2 liters of your choice of broth (vegetable and chicken both work well)

French bread, cut into cubes

½ teaspoon ground cumin, or to taste

Lime wedges, to serve

Instructions:

- Clean and rinse the lentils and place them in a large pot. Cover with an inch of water and add a teaspoon of salt. Bring to a boil then simmer for 5-7 minutes. Strain.

- In a skillet, brown the chopped onion and carrot in a tablespoon of butter.

- Add the onion, carrot, lentils, tomato, and broth to the pot, if using an immersion blender. Otherwise, add them all to a regular blender, leaving the buttered skillet as is. Blend until smooth.

- Return to pot if necessary, then reheat and add salt and cumin to taste. Simmer on low heat for 5 minutes.

- Toast the cubes of bread in the buttered skillet; use these as a garnish.

The soup makes an appearance in Nile Nightshade’s conclusion, which looks back over the sweep of the book to ask: how, exactly, did tomatoes become Egyptian? And what can we make of that transformation?

The book’s opening chapters trace tomatoes’ appearance in the historical record, from their probable Ottoman-era introduction to Egypt (Chapter 1) to their steadily increasing presence in Egyptian botanical works, agricultural manuals, cookbooks, markets, fields, and kitchens over the first half of the twentieth century (Chapter 2). Subsequent chapters delve into the question of how tomatoes, once they were physically present in Egyptian territory, made themselves at home in Egyptian culture & society as objects of political, cultural, and emotional importance (Chapters 3–6). The book’s conclusion, “How Tomatoes Became Egyptian,” takes up the concept of the “baladi” to explore the tensions and contradictions entailed in tomatoes’ transformation from a new ingredient into a local one.

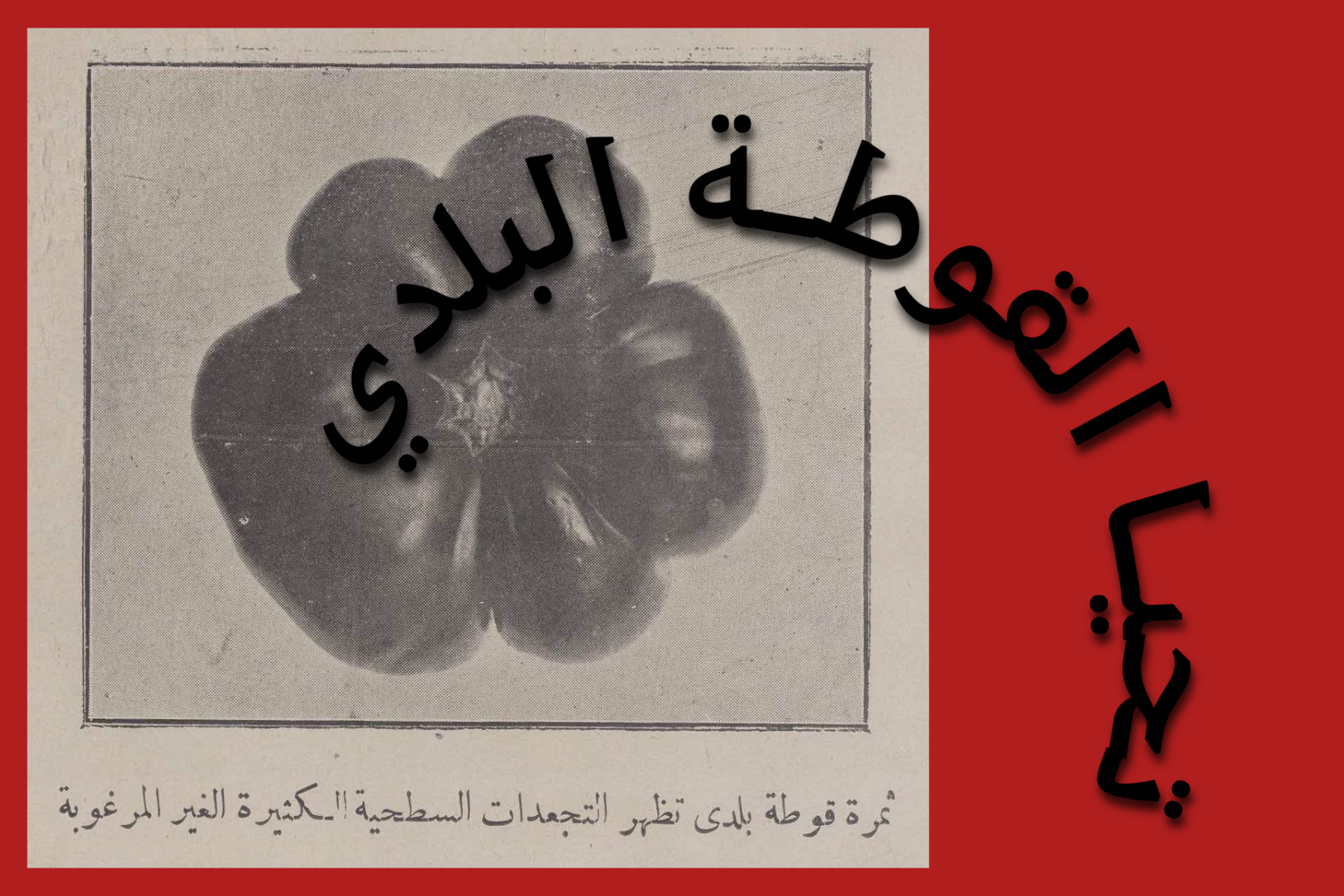

“Baladi” literally means “of the country.” It is often used to denote that something is local: an heirloom or heritage variety of vegetable or breed of livestock, or a recipe––like the one above––associated with home cooking. In some instances it distinguishes the local from the foreign, but it also operates as a label that can transform the foreign into the local, as the case of the “quta baladi” (baladi tomato) attests.

By the 1920s, agricultural sources were referring to the “baladi tomato” as the most commonly cultivated variety in Egypt. In other words, by this point there was a variety of tomato that Egyptians not only cultivated in large numbers, but considered to be uniquely Egyptian. Agricultural experts and policy makers were also swift to point out that the beloved quta baladi was not optimally lucrative or productive compared to the more profitable and industrially suited imported varieties from Italy and the US. Despite the complaints of agronomists over the decades, however, the baladi tomato persists to this day, here and there, in fields and markets and memories of how good tomatoes used to taste.

The complexities of what it means to be “baladi” are personified by the lentil soup recipe above. It is based on a recipe from a classic Egyptian cookbook published in the 1940s, which includes two “baladi” lentil soup recipes and one “afranji” (foreign or European) one. This mix of recipe styles is common throughout the cookbook as well as the wider genre of domestic cookbooks it belongs to (Chapter 4). So what does it mean to mark something as “baladi” in a recipe collection that is also full of French-style sauces and European pastries? In the book’s conclusion, I propose that the juxtaposition of baladi and afranji lentil soups suggests to the reader: “learn a European soup recipe, but don’t forget where you came from” (186).

Lentils, incidentally, have been a constant in Egyptian cooking for millennia. But as is the case with so many other locally rooted dishes, the canny tomato has made its way into lentil soup recipes in many Egyptian homes (although this isn’t reflected in the written recipe referenced above, which was published at a time when tomatoes were still a vegetable on the rise). In one of the oral history interviews I conducted as a part of my research, a grandmother I call Hanan (all names have been changed) gave me her own take on a baladi lentil soup recipe. Unlike the precise list of ingredients specified Nazira and Osman’s written recipe––which had been published around the time she was born––Hanan offered a number of possible customizations and additions to the recipe to reflect personal preferences: garlic and parsley for seasoning, carrots to enhance the soup’s color, or a tomato to punch up its brightness and acidity. The more I asked home cooks about the role of the tomato in Egyptian home cooking, the more I learned that the addition of a grated or chopped tomato was not uncommon in many Egyptian dishes that had predated the tomato’s introduction, like mulukhiyya. In a cuisine that has long prized brightness and acidity, the tomato handily assumed the role not just of a vegetable or a sauce base, but a seasoning.

In this sense, this lentil soup recipe speaks not only to the themes of the book, but to its methods. The narrative moves back and forth between textual sources, like the wide variety of modern print cookbooks published in Egypt, and ethnographic ones, like interviews conducted with the women who were the target audience for those books (the latter feature particularly prominently in Chapter 5). This approach to research produced both overlaps and divergences; different forms of culinary know-how––written and embodied––sometimes confirmed and sometimes contradicted one another. The result is that Nile Nightshade underscores the difficulty of mapping cultural or culinary material onto neat binaries of foreign vs. local, modern vs. traditional, baladi vs. afranji, or industrial vs. heirloom. Even this “baladi” soup recipe draws together the ancient lentil, the early modern tomato, and croutons made from the far more recently introduced French-style bread.

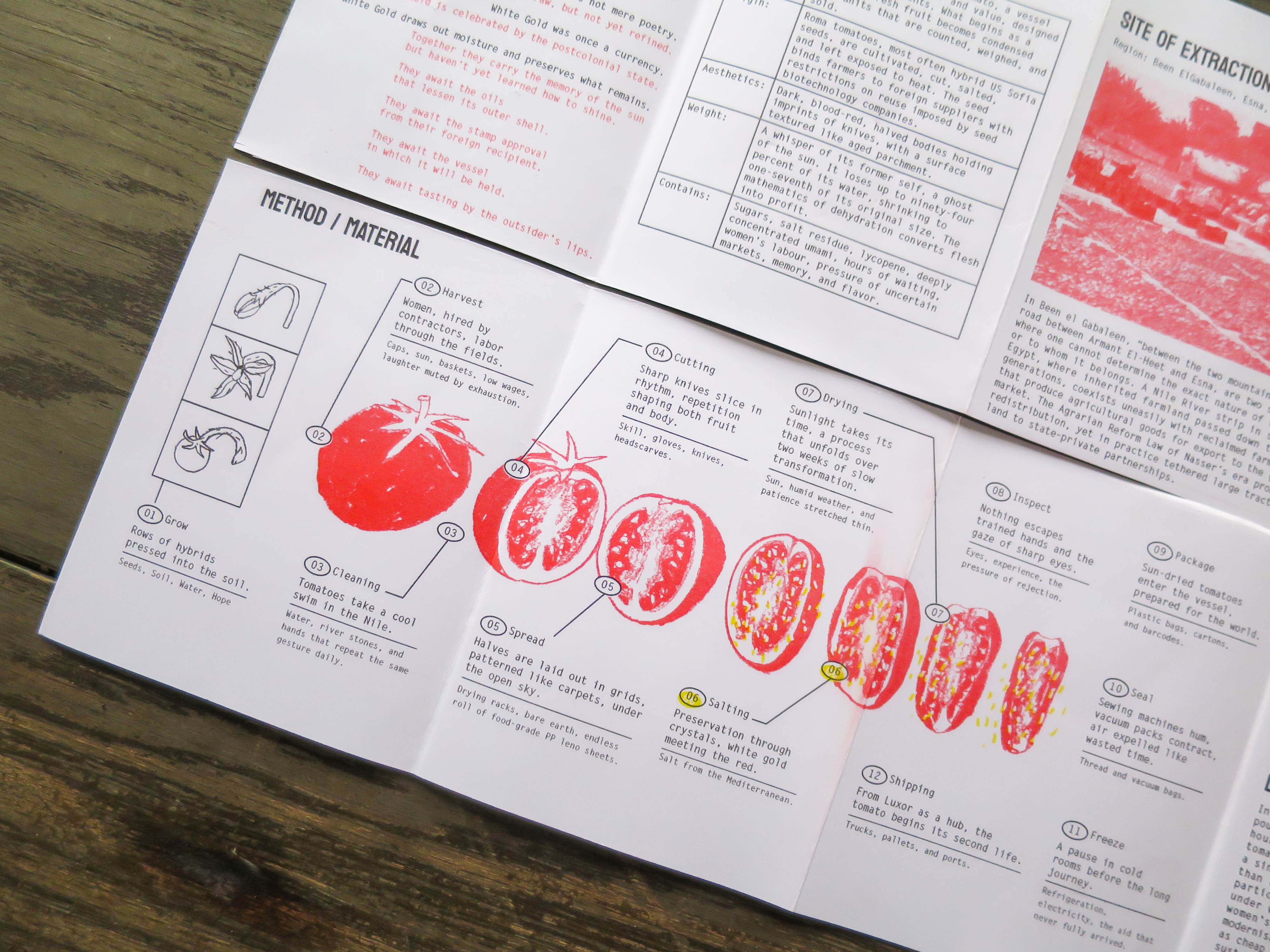

But it’s one thing to analyze how these disparate strands converge in a recipe. It’s quite another to understand how they jostle for space in the political economy of agricultural production. It’s not only local preferences or cooking styles that determine what crops are produced in Egypt, but material constraints, state policies, and the dictates of global markets (Chapter 3). Artist Yasmine El Meleegy’s work, which I discuss in the book’s conclusion, explores these tensions through sculpture and installations. Her Future Farms (Organic) features a set of fiberglass tomatoes of different shapes––from the popular baladi to the smoother, more uniformly shaped varieties grown from more recently imported hybrid seeds.

El Meleegy's most recent work (currently on view at The Mattress Factory), Red Gold, explores a USAID-funded project that promoted the production of sundried tomatoes for export in Upper Egypt––in a region once known for its lentil production. Sundried tomatoes do not figure into local Egyptian cooking practices, but they are far more lucrative for farmers than many products that do.

As El Meleegy writes of the project in the exhibition’s companion publication: “Preservation became not simply about prolonging the life of the tomato, but about prolonging a system that diverted land away from wheat, lentils, and fava beans toward ‘red gold’ for foreign consumption…the goal was not domestic nourishment but the synchronization of Egyptian land with distant appetites.” Of course, with the effective shuttering of USAID this year, the future of the project is now in question. However beautifully they complement one another in lentil soup pots all over Egypt, tomatoes and lentils do not blend so easily in the realm of production, where one has replaced another in local agricultural practice.

The chapters of Nile Nightshade suggest that we can’t fully understand culinary cultures without looking at the material factors that shape them––and, conversely, that in studying the politics of food systems we should look beyond the metrics of caloric needs and trade balances to consider cultures of taste and flavor, too. At its heart, the book is an attempt to braid together narratives that we tend to treat separately. We know by now how central food is to our understanding of the communities and places we belong to; but what does it mean to fully account for whose land, water, labor, and know-how nourish the food cultures that feed us?