Animals and the History of Natural History

Rebecca Woods (University of Toronto) and Anya Zilberstein (Concordia University, Montreal) are historians with research interests including the history of science and the environment, and the cultural histories of animals and human-animal interactions. They recently collaborated to guest-edit Creatures of History—a special issue of UC Press’s journal Animal History which examines the role of animals in shaping scientific knowledge-making.

UC Press: We’re incredibly excited about this year’s launch of Animal History. Thank you for being a part of the inaugural volume!

RW/AZ: We’re gratified to be part of it, especially because it’s perfect timing for this collection of essays. Although each contribution is a stand-alone article, the collection came together as a tribute to our mentor Harriet Ritvo, whose scholarship initiated–and set the highest standard for–animal history. There’s no question that Ritvo’s works will be cited, at a minimum, in every volume of Animal History for a long time to come!

UC Press: Your new Animal History special issue centers on the role of non-human animals in histories of natural history. What was the impetus for this focus?

Scholars sought and found animals in scientific spaces–such as the laboratory and the zoo–that had emerged from natural history, but whose natural historical origins had been forgotten or were obscured.

RW/AZ: This focus is also undeniably an artifact of Ritvo’s influence. As two of her former students, we both situate a good part of our research in relation to the history of the environmental and earth sciences, most of which emerged from natural history. Beyond this, we felt that the defining role of natural history as a foundation for how we understand nonhuman animals merits more directed scholarly inquiry. Animal history has long intersected with history of science, with some of the earliest and most exciting strands of animal history emerging out of that confluence. Alongside cultural historians, much of the early work in animal history came from historians of science: Karen Rader’s Making Mice; Robert Kohler’s Lords of the Fly; Nigel Rothfels’s Savages and Beasts; Anita Guerrini’s Experimenting with Humans and Animals; Donna Haraway’s Primate Visions; and of course, Harriet Ritvo’s work (especially The Animal Estate and The Platypus and Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination). Scholars sought and found animals in scientific spaces–such as the laboratory and the zoo–that had emerged from natural history, but whose natural historical origins had been forgotten or were obscured. Basically, from the early modern period to the early 20th century, natural history was the science of animals. The essays in this special issue are not only reminders of that original role for the discipline, but should also spur further inquiry into the subject.

UC Press: Your introductory essay and Janet Brown’s article “Charles Darwin and Cats” pose the hypothetical: what if Charles Darwin were a cat person? Would the history of natural selection read differently?

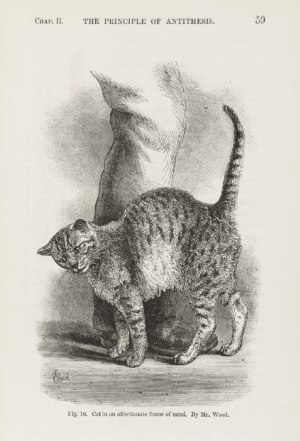

RW/AZ: That counterfactual, which is a subtext of Janet Browne’s piece in the volume, is interesting to consider as a thought experiment. It asks us to take seriously the influence that animals have had in shaping ideas, including ideas of outstanding influence, like Darwin’s contributions to evolutionary theory. Browne is arguably the foremost Darwin scholar of the last several decades, and her remarkable body of scholarship has carefully detailed where and how his evolutionary ideas emerged and developed. Darwin’s idea of “natural” selection was based on his observations of artificial selection: the ways in which pigeon and cattle breeders sought and reproduced desirable traits across generations of animals. His understanding of the origins of human emotions came, in part, from his observations of animal emotions, especially the behaviors of his pet dogs. What would evolution, and by extension natural history look like had its most influential architect been a cat lover? Probably a little less domestic, perhaps a touch more predatory, with nature redder in tooth and claw. But as the collection shows, cats are in fact everywhere in natural history right up through the twentieth century, so they have done pretty well for themselves, despite Darwin’s unfortunate lack of interest in felines.

UC Press: Tell us about some of the other research featured in the special issue.

RW/AZ: The issue features exciting new work from both established and emerging scholars, all of which demonstrates how nonhuman animals, from the very small to the very large, shape the knowledge systems designed to shed light on their very being. Jessica Wang’s study of Ceratitis capitata in global circulation shows how even a seemingly insignificant or simply bothersome creature like the Mediterranean fruit fly dramatically shaped scientific and commercial culture. Alison Laurence’s essay explores revisions to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s dioramas depicting Greater L.A.’s urban wildlife, revealing how the displays both reflected and influenced evolving understandings of predators–specifically coyotes and cougars–from troublesome pests to valued natives of the megacity’s habitats at the beginning of the 21st century. We also love Whitney Barlow Robles’s critique of the tension between scientific research and biodiversity by looking at how the taxonomical history of sea sapphires (tiny, iridescent crustaceans, a species of copepods) ultimately contributed to their undoing. Roble’s essay, with its fabulous range and illustrations, also touches on the fennec fox and other hard-to-classify figures in the history of natural history.

We see the concept of nonhuman cultures and their historicity as one of the most significant and fascinating recent developments in the field.

UC Press: It’s clear from your collection that historians have underestimated animals—underestimated the paradigm shift, the changes in how we understand them; and underestimated how animals themselves have informed scientific knowledge. Where do you see animal studies heading as a field of historical inquiry?

RW/AZ: We see the concept of nonhuman cultures and their historicity as one of the most significant and fascinating recent developments in the field. Perhaps not surprisingly, animal historians’ interest in this topic is emerging in dialogue with contemporary scientific research on particular animal communities. This idea, which comes out of recent work in ethology and animal behavior, confirms that individual animals and animal communities have always operated on far more than bare instinct, and that traditions, practices, and even sometimes rituals (as, for example, in the complex case of elephant mourning) are communicated, learned, and transmitted across generations. Animal historians are drawing on this scientific insight, triangulating between ethological theory, field observation, and the historical record, to show how animals produce culture in an intergenerational, even historical, mode—culture that is marked by familial relations but that may also extend beyond them.

Our special issue offers two essays on nonhuman cultural history, both of which are haunted by processes of deracination. Shira Shmuely and Tamar Novick demonstrate how the trauma of the live animal trade in the 20th century eroded orangutan cultures of maternal care, with catastrophic consequences for young orangutans born into captivity far beyond their native Borneo. Sandra Swart goes further, arguing that the lions and peoples of South Africa have historically shared culture, adapting to each other’s needs and preferences, enabling them to coexist across generations–another form of animal culture devastated by colonial practice in the 20th and 21st centuries, but which Swart suggests, may be a guide for our shared, more-than-human future.

UC Press: Thank you for this important contribution to the history of animals, and to Animal History!

RW/AZ: Thank you! We’re delighted to see this collection in print, and thrilled to be part of the inaugural volume of the journal!

Animal History publishes cutting-edge historical research on the histories of animals and human-animal relationships, documenting the impacts animals have had on global histories, cultures, languages, technologies, and environments as well as the impacts that humans have had on animals and their pasts, cultures, and lives.