Studying the Only Known Native Hawaiian Whaling Captain: A Q&A with Travis Hancock

Kānaka Maoli, or Native Hawaiians, have a long history of skilled seafaring. In the early nineteenth century, large numbers of Kānaka Maoli leapt into the global economy as part of the new commercial whaling industry, even though killing whales was not traditional to Hawai‘i.

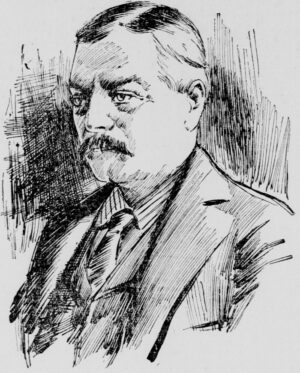

Kāpena (Captain) George Gilley was the first Native Hawaiian known to lead whaling expeditions. His expansive career shows the willingness and ability of Kānaka Maoli to thrive in the new whaling industry, to critically adapt to change, and to not just survive but excel within the confines of so-called modernity. Historian and curator Travis Hancock uncovered Gilley’s life story in the Pacific Historical Review. His article, “The Many (De)colonial Lives of Kāpena George Gilley” is a co-winner of the Abbott-Johnson Award of the Pacific Coast Branch–American Historical Association.

What was your reaction to winning this award?

My first thought, of course, was that it is a great honor to be recognized. Second, I thought about the ways this recognition might increase awareness of George Gilley, which was a driving force for researching and writing his story. I can only hope that in time his name will once again travel as widely as he did, and that his story will serve as a resource to all kinds of people, from scholars looking to further crucial narratives of Indigenous mobility to descendants of the early colonists on the Bonin Islands, where Gilley was born.

In so many ways, this article would not exist without those families. Not only did Native Hawaiians form the bulk of the 1830s community there that produced George Gilley, but in the 2020s their diverse descendants have formed social media communities through which they pool research, ask questions, and at times graciously assist outsiders, like me. When I started writing about Gilley some years ago, they asked for my sources, pointed me to others, and disabused me of erroneous impressions. Those exchanges drove much of the work, which was further helped along by feedback from good friends, colleagues, and peer reviewers.

What was it like to write about someone while communicating with descendants?

To this day it is hard to confirm whether or not there are direct descendants of the captain, but it is not my place or intention to decide that. Either way, communicating with relatives certainly increases the meaning of the work. It also raises the stakes, as it drives home the reality that writing history has consequences for living people today. This is always heightened with Indigenous histories, which have not always fared well in non-Native hands. As a white scholar, a haole, I strive to stay vigilant of my positionality and privilege, and make efforts to center methods and worldviews appropriate to Indigenous actors, as put forth by Indigenous scholars, even as I write in English, engage settler archives, and follow models of empirical history. The tension between those practices was often on my mind as I researched Gilley, whose race and indigeneity mattered greatly to some people he encountered, and seemingly not at all to others. That variation likely persists to this day, even among relatives.

Meanwhile, it remains difficult to say what being Native Hawaiian really meant to Gilley himself. His actions economically supported the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, yet did not always resist foreign empires and settler capitalism, or fit into narratives of Indigenous solidarity. But the pervasive structures of settler colonialism simply don’t always allow for those things. As I tried to show, Gilley was remarkable for finding ways to exist and even thrive through decades on the front lines of violent change in the Pacific, but he was also one of many, many survivors whose stories may be overlooked for their apparent complicity in that change. While being the first Native Hawaiian whaling captain made him exceptional, being a Native survivor with a complicated story may make him far more typical.

Can you discuss some memorable discoveries during the research process?

I’ve been aboard Gilley’s boat for about a decade, and I never know where he is going to take me. That is partly a joke, but it gets at his real power to generate archives, the loggings and traces of his life, through his ‘oihana, his skilled labor. One of the arguments of my article is that just because historic Indigenous actors weren’t always writing things down—often the preferred method of record-keeping among their colonizers—doesn’t mean they didn’t craft their stories with great agency.

As I trained myself to see how legible an elusive figure like Captain Gilley could be, I often found myself feeling transported, even to multiple places at once. I clearly recall sitting in Colorado on a video call during the pandemic, chatting with a librarian from the University of Washington’s special collections and taking screen shots as she patiently turned pages of a small, loose-leaf manuscript handwritten by a man who visited the Bonin Islands in the late 1890s. In that confluence of times and places, it was surreal to lay eyes, through a grainy tablet screen, on one of the only primary sources clearly identifying Gilley’s Native Hawaiian mother, Fanny, alongside notes suggesting she could have been as young as twelve when she left Hawai‘i for the Bonin Islands. To this day, the research continues, as I refuse to disembark. A recent re-examination of seamen’s records in the Hawai‘i State Archives confirmed my earlier inferences that Gilley had started making whaling voyages to the far north by the late 1850s.

What is next for you?

The first drafts of this article started out when I was a student in the University of Utah’s history PhD program, which I am glad to say I have since completed—I am now working on a book, based on my dissertation. The book is focused on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Hawai‘i, and it looks at how the local white community used science to maintain sociocultural power, while forfeiting some political control to American territorialization. As in the Gilley article, I frequently emphasize the ways Native Hawaiians refused to be passed over by those changes, and instead engaged foreign ideas to hold power within their territory and have a say in their own future.

We invite you to read Travis D. Hancock’s award-winning article, “The Many (De)colonial Lives of Kāpena George Gilley” for free online for a limited time.

Print copies of PHR's Winter 2024 issue (issue 93.1), in which the article appears, as well as other individual issues of PHR, can be purchased on the journal’s site.

For ongoing access to PHR, please ask your librarian to subscribe and/or purchase an individual subscription.

We publish PHR in partnership with the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association.