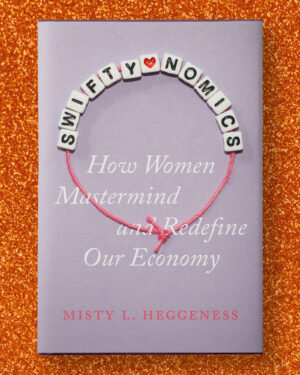

An Exclusive Look at "Swiftynomics" by Misty Heggeness

UC Press is delighted to offer an exclusive excerpt from Swiftynomics: How Women Mastermind and Redefine Our Economy by Misty Heggeness.

Excerpt from "INVISIBLE LABOR: I Dare You to Come for My Job"

Invisible String

The field of economics is flush with macroeconomic models predicting how labor markets and prices will react to policies and structural changes in the economy. Even though the field in modern times has been predominantly dominated by men who love math, and, in historical times, by men who ignore the economic activities happening right under their noses within households, there are economists today and in the past who care deeply about creating and adapting models to incorporate structural realities driven by social norms and unequal endowments.

There are entire buckets of economic literature devoted to how increasing women’s economic activity outside the home and their given resources at birth or marriage can increase their power over household resources. These resources can shift negotiation power over the household budget and can influence whether the budget is used to pay for cleaning, meal preparation services, and schooling or extracurricular programs for their children. Policies focused on equalizing gendered control over resources have improved women’s ability to thrive and succeed outside and inside the home.

Shelly Lundberg is known for her contributions to the economics profession by developing theories about how individuals within a household bargain with each other over limited resources to decide how much to spend on clothing, food, or education for children. Studies in low-income countries have focused on assessing the very basic nature of this type of bargaining and have come up with empirical evidence suggesting that women are more likely to spend resources on household goods like clothing for children, education, or food than men. These studies also find that when men are in control of household resources, they spend a larger portion of the household resources on personal or private goods like tobacco or alcohol.

When I discuss this research with my colleagues from middle- and high-income countries, the rebuttal (mostly from male economists) is swift and sharp. Those living in high income countries tends to think their behavior is not linked to this same type of sexist behavior observed in lower income countries. They often argue that dads in high income countries would equally spend on the education of their children as women would. However, that rhetoric lands on deaf ears when we look at the research conducted in middle- and high-income countries. Mothers are still more likely to invest in others rather than themselves – or in themselves through purchasing goods and services that reduce their domestic care load.

I see this reverberate in my own family. My spouse cares deeply about gender equity and engaging in decision-making as equals, yet our preferences are different. My tolerance for purchasing cleaning services or meal prep boxes is much different than his – mostly because I value my time, a scarce resource, in a different light than he does. Meanwhile, my spouse has owned up to three triathlon bikes at one time. His triathlon bikes, a private good, are the equivalent of cigarette and alcohol consumption of prior economic studies in low-income countries.

It turns out, at the end of the day, gendered preferences in prioritizing resource allocation and spending within households is a legitimate universal issue across the globe. While there is variation in individual preferences within gender, when we look on average, gendered trends exist. Because of this, policies like divorce laws dictating who gets control of resources when families split have influence in determine the allocation of resources in intact families. A quick change in divorce policies that shifts control of family resources can have profound effects on overall social welfare and community wellbeing.

Divorce laws are not the only policies that can shift a family’s economic investments and outcomes. The same is true for policies and social norms that make it easier or more feasible to get a high-quality education. Increases in women’s education and more family-friendly policies in the workplace often correlate with increases in women’s labor force participation.

Policies that make it possible for caregivers to work outside the home increase household investments in the next generation by putting more direct economic resources in the hands of primary caregivers. Overtime, we have seen this play out both in increasing educational attainment of women making them more marketable in the labor market and in policy movements towards investments in topics important to family caregivers who work, such as increased supports for policies that support the childcare and eldercare industries. Still, there is much work to be done.

Often what is lacking in the argument for public supports or public-private partnerships in markets that help caregivers thrive, like childcare, is data. Data highlighting the return on investment to high-quality early childhood education as it relates to economic outcomes for caregivers like their lifetime earnings, household earnings, and wealth or data linking caregivers in the workforce to macroeconomic indicators such as economic growth. These statistics connecting investments in caregivers to economic outcomes are, in some respects, lacking today because we live in a society and culture that takes care for granted. This is the challenge of the 21st century, and it won’t be solved unless we all speak up and demand better of both ourselves, our friends, families, and communities, and those who represent us politically.

We will know when we succeed. When we do, the childcare industry will be equally prioritized in hard economic times. Bailout scenarios for businesses considered “too big to fail” will include childcare in the discussion. And threats on the childcare industry will be as easily resolved as they have been for the airline or automobile industries in the past. We will know because childcare will be accessible and affordable for all. Parents will have more choice in how they want to live their best life given the resources available to them. Economic growth will flourish. There will be less crime. And, if we are lucky, caregivers will be happier or at least more content, less stressed, and have better balance in their lives, which inherently will increase wellbeing for all.

evermore

Some argue that the modern-day school calendar was developed to help farmers who needed their children home and working in the fields when planting and harvesting was at its most intense. Others find that the calendar was based on urban elite preferences around vacationing to cooler places in hot summer months. None of these reasons had anything to do with the best intentions for the children or their care providers. Roads, trains, and flight patterns were developed to facilitate trade between cities, states, and nations – not to help children get safely to school or caregivers safely to parks and daycares. In the same light, the labor market was not built with caregivers in mind.

Modern economies were designed with the expectation that workers get to and from work with ease. There is little consideration for employees with childcare needs or schooling for their children. The typical work day was designed by the employer, usually care-privileged themselves. Systems to advance at work were built to keep those with power and privilege on top.

Care privilege belongs to those of us who have someone else taking care of our care and maintenance needs. Modern economies were built by and for those with care privilege. Individuals with care privilege have historically been men.

What happens to women and caregivers when they interact with an economy originally built for men and those with care privilege? They hide their caregiving roles from employers for fear of not being taken seriously. They worry and stress. They accept less leisure and sleep relative to their care-privileged counterparts. They work harder and are usually rewarded for it with less pay and slower paths to promotions. Maybe this is your reality. If it is, you are not alone. This is the reality of most caregivers today who work in the formal labor market.

An average workday is stereotypically from 9am to 5pm, at least according to screen writer Patricia Resnick who wrote the script about women and paid work for the 1980 film 9 to 5. Before the work day begins, caregivers often have already worked anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour getting their loved ones ready for the day. One study found that yearly parents spend a total of 139 hours, more than three weeks of a fulltime work week, getting their children ready for school in the morning. This includes waking up, clothing, feeding, and transporting small children to daycare or school. It often also includes preparing lunchboxes with sandwiches, fruit, something starchy, and a juice, milk, or water.

The caregiver does not have the luxury of heading straight into the office from home. They make at least one pit stop, often multiple, to drop of small children at their chosen destination for the day. Dropping off almost always requires getting out of the car metro, or bus with said child, their lunchbox, and bag of necessary items for the day (often a backpack if they are school age). The caregiver then walks the child into said daycare or school, signs them in, talks with the staff, helps the child take off their coat and put their things into a cubby, leaves – sometimes with a stressed child crying about being left, and gets back to their mode of transportation, and finally drives to work.

By the time they get to work, their care-privileged colleagues, many of whom woke up, showered, (worked out?), dressed themselves, ate breakfast, and drove straight to work, are fresh and ready to start their workday. The caregiver, on the other hand, is already tired, their hair in disarray. Maybe they had to drive across town to drop their child at daycare. Maybe they did not sleep through the night. The caregiver is often the first woken up during nightly disruptions from small children who cannot sleep or for whom the only way back to sleep is next to the caregiver – often disrupting the even flow of deep sleep needed by the caregiver to feel fully rested and function the next day.

At any point in the workday a caregiver can be randomly disrupted by a daycare or school, often calling to explain a situation related to biting or a fall off school yard equipment. By mid-afternoon, the caregiver might be aware of transportation needs from school to an after-school program or, in some cases, may need to take time off mid-afternoon to pick up a child from school and transport them back home. The caregiver is often mindful of the close of the workday as they are usually rushing to get out and make it to daycare or the afterschool program to pick up their child before it closes. Caregivers arriving late for pick up can experience steep penalties up to $2 per minute late, increasing their stress to leave work on time and crossing fingers there are no traffic delays driving lateness.

At this point in the day, the caregiver’s third shift starts. Unlike the care privileged who may leave work and head to a happy hour or home to kick off their shoes and crack open a beer to watch sports or the news until their dinner magically appears on the dining room table, the caregiver arrives home usually to the madness of finding snacks for their tired and cranky children while simultaneously changing out of work clothes and prepping dinner. After dinner there is dinner clean up, baths for children, and some sort of bedtime routine. By the time the caregiver crawls into bed, she (or he) often has had minimal personal free time to recharge and energize. Only to start the cycle all over again when she (or he) is woken up a few hours after falling asleep to a small child who has just had a nightmare and wants to snuggle their way back to sleeping next to the caregiver.

It is difficult to come across any sector of our formal economy developed with the caregiver in mind. Since women disproportionately carry the load of caregiving in many societies, most economies were developed without consideration for women’s needs. As women’s educational attainment continues to increase and women’s role in the economy outside of their homes in paid employment became critical for family wellbeing, an economy built for the care privileged has become ever more glaring. Post-pandemic, labor force participation of mothers has accelerated making the issue even more visible.

Caregivers engaged in invisible labor are exhausted. But just how exhausted? Nations do not regularly report statistics on the number of hours engaged in unpaid family work in our homes, hours that include washing dishes, making meals, and cleaning. In fact, the U.S. did not even start collecting data on how people use their limited time until 2003.

Not developing and reporting these statistics means we do not fully understand how increased mothers’ labor force participation and time spent caring for their family post-pandemic has impacted their mental health and that of their family members. There are, after all, only 24 hours in a day and something usually has got to give for caregivers when labor force participation increases – it’s usually their mental health.

Look What You Made Us Do

Today women think twice about having children. Many are choosing not to have them. In 2022, 17.6% of women in their 20s had children under age five, this compared to 46.3% in the 1970. Young women have done the girl math and some have calculated that children are too expensive or too disrupting to their lifestyle and career goals. It is not only that women are delaying births due to advancements in educational attainment, reproductive health, and increased economic independence. Average age at first birth has increased to 27.3 years old. In addition, women are having fewer total children in their lifetime compared to previous generations.

According to an opinion piece written by economist Dean Spears and published in the New York Times on September 18, 2023, children born today are likely to see global population peak before it begins a potentially steep descent. That is because, as Dean argues, families across the globe are choosing to have fewer children. And, as Dean is quick to point out, very few, if any, countries have ever recovered to a population rate above the replacement rate of 2.1 once they go below it.

Economists place the cause of this fertility decrease on increased educational attainment and improvements in health and longevity primarily driven by technological innovations like the pill, intrauterine devices (IUDs), the pacemaker, and vaccines. Because higher education leads to higher incomes and a focus on a career rather than a job, Dean argues that the replacement rate is not likely to increase since more and more women and parents will continue to struggle balancing career with the needs of family.

When it comes to living in an economy built by men, Dean and I agree that population rates are not likely to increase given the current state of expectations around how we work and how we live. But there is a way to increase the number of children families have if we so desired that does not involve taking away the reproductive health rights of women. We could re-envision our economy, priorities, and expectations around how we do work and family.

We could create a Barbie Land-style society, call it the Fertility Land, that encouraged a strong and healthy balance between career expectations and family life. This economy would provide a bold set of care policies. Instead of it being cost prohibitive to have and raise children, policies would strengthen families’ ability to have multiple children, should they wish, and stay engaged in their careers and jobs. In this economy, childcare would be affordable and, for those who chose to take the lead on supervising and raising their small children in the home, stipends would be available that value the unpaid family care work involved in raising the next generation. In Fertility Land, men would increase their activity and engagement in childcare and unpaid domestic work within their homes. They would slow down in the workplace and, vice versa women would accelerate – causing more equality and reductions in the gender wage gap.

Even without this made-up society, Dean’s predictions may still not come true. They remind me of the fallacy of population decline circulating among demographers and economists at the turn of the 19th century. In 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus published a book titled, An Essay on the Principle of Population. In it, Thomas argued that increasing food production through innovative technologies improved well-being of the population but also led to exponential population growth with a continued risk of a lack of sufficient food for this exponentially expanding population, which would eventually lead to starvation of a population unable to feed itself. This model (driven by math!) proved wrong at a global level. There is still enough food in the world to feed the globe, should our policies allow it.

Thomas’ theories, however, led to the identification of something called the Demographic Transition, which has been observed in most countries across the globe at this point. It starts from a population with high fertility and high mortality. Technological innovations and growth lead to decreases in mortality rates through improved health. This leads to a natural increase in the population as birth rates are still high and individuals are living longer and dying less. Eventually, the technological advancements and decreased death rates lead to increased economic growth and productivity, making having children more costly (because of the loss of earnings from moving away from paid work to care for children), which then drives a decrease in birth rates. Eventually populations end up in a stage of low fertility and low mortality – which is where many countries are today.

Neither Thomas’ theories of population growth nor Dean’s warnings of population decline considered the choice a society led by women and caregivers might take us. Like Adam, Thomas and Dean’s theories were driven by modern economic thought that markets are efficient with their invisible hands. None of these theories speak to the roles community, government, and policy infrastructure can play in the health and wellbeing of a society and the workers and caregivers driving its economy.

Learn more about Swiftynomics.