1,301 Results

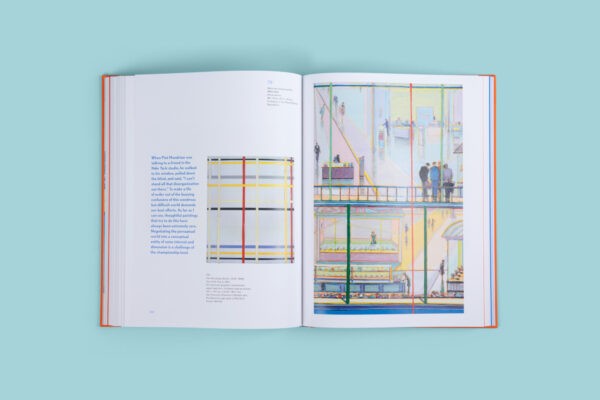

A Look Inside "Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art"

May 09 2025

A fresh reexamination of Wayne Thiebaud as a self-described “art thief."

Read More

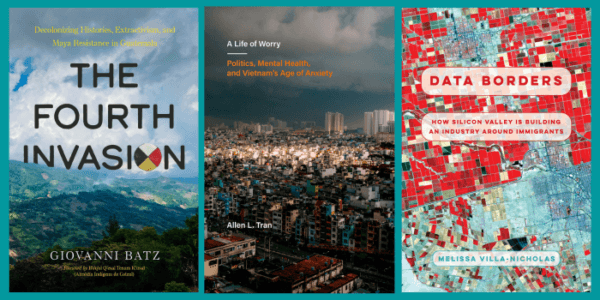

UC Press April Award Winners

May 07 2025

UC Press is proud to publish award-winning authors and books across many disciplines. Below are our April 2025 award winners. Please join us in celebrating these scholars by sharing the news!

Read More

Q&A with David Feltmate, Editor of the "Journal of Religion and Popular Culture"

May 06 2025

Meet David Feltmate, editor of the "Journal of Religion and Popular Culture," which is now published by UC Press.

Read More

From the UC Press Journals Archives: Remembrances of the Vietnam War

Apr 30 2025

The pages of UC Press’s journals have examined the War from a myriad of angles, from all sides of the conflict–its global economic and political impact, the role of student activism, memory in small-town America, and more.

Read More

"Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos" Announces Christian Zlolniski Award for Best Early-Career Article

Apr 29 2025

MS/EM's early career article award, which has been renamed in honor of its most recent emeritus editor, is now accepting self-nominations.

Read More

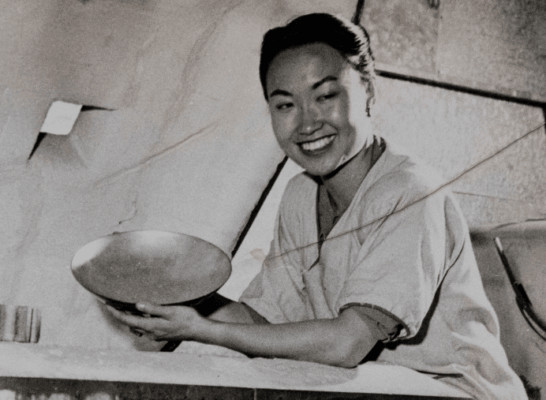

New from "Pacific Historical Review": Jade Snow Wong, Women’s Self Defense, Patricia Derian’s Humanitarian Legacy

Apr 28 2025

A preview of the Spring 2025 issue of "Pacific Historical Review," which takes readers to World War II, the Cold War, and beyond.

Read More

A Conversation with Nina Peterson and Katherine Guinness, guest editors of “Aesthetics of Perplexity,” a Special Issue of Afterimage

Apr 24 2025

Afterimage's new special issue, "Aesthetics of Perplexity," is interested in examining perplexity as an aesthetic category, in which the experience of confusion or bewilderment can be harnessed as an artistic tactic.

Read More

JSAH Virtual Issue: Architectural History of Atlanta and the Southern United States

Apr 23 2025

The editors of the "Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians" invite you to read a virtual issue on the architectural history of Atlanta and the southern US, which has been published in conjunction with #SAH2025 in Atlanta.

Read More

Case Study Examining Deep Energy Retrofits for Affordable Housing Wins Top Prize in 2024 CSE Prize Competition

Apr 22 2025

Case Studies in the Environment Prize Competition's 2024 winning article, from authors Lia Downing and David Hsu, explores the case of Brooklyn's Casa Pasiva green energy retrofit project.

Read More

Help Us Grow Our FirstGen Program!

Apr 22 2025

UC Press has great news to share about FirstGen program growth and seeks your support for its continued success. Here’s how our program has benefitted first-gen authors so far.

Read More