By Jan Bardsley, author of Maiko Masquerade: Crafting Geisha Girlhood in Japan

This guest post is part of our #AAS2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit to learn more.

“What kinds of geisha stories exist these days in Japan?”

“Are Japanese people reading novels and seeing movies about geisha, too?”

These were the questions my students asked at the end of our 2002 seminar, “Geisha in History, Fiction, and Fantasy.” Our entry into Geisha studies had been wide-ranging, covering kabuki plays, ukiyo-e prints, Japanese films, and short stories.

Wikimedia Commons.

We also explored “geisha girl” fantasies abroad from late 19th-century fiction to Memoirs of a Geisha, Hollywood films, and Asian American guerrilla art. We saw how Japanese representations of geisha, though often different from Euro-American ones, spoke equally to their cultural moment. Take the 1890s, for example. Japanese intellectuals, stirring cultural nationalism, celebrated geisha as icons of Japanese beauty while advocates for women’s education protested against the sexual nature of the “flower and willow world.” In London, however, the 1896 musical comedy, Geisha–Story of a Teahouse imagined an Anglo woman in geisha masquerade as means to attack the New Woman’s movement in England. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Japanese media drew attention to beauty queens and fashion models as symbols of successful postwar reforms, while Hollywood movies used geisha characters as lessons in femininity for American women, seen as having grown “overly assertive” in wartime. But what was the case in Japan now?

Searching for the answers to that question became a quest. Over many trips to Kyoto, I realized that the geisha figured little in the contemporary cultural landscape. It was her teenage apprentice—the maiko—who was the twenty-first-century star.

Fictional maiko played the lead in films, novels, TV dramas, and manga. It was the maiko who inspired tourist experiences and souvenirs. Her celebrity aura motivated teens from around Japan to venture to Kyoto to try to become (or at least cosplay as) maiko themselves.

I began analyzing the meanings attached to this millennial maiko and the multiple representations of her. What I found pointed to competing views of the geisha, and more broadly, to visions of girlhood in Japan.

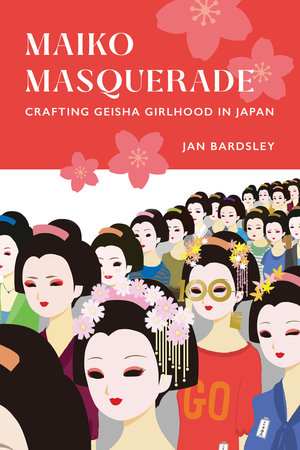

My new book Maiko Masquerade: Crafting Geisha Girlhood in Japan takes readers through a host of different maiko texts produced mainly in the 2000s: etiquette guides, first-person accounts, popular histories, films, and manga. My book traces how the maiko, long stigmatized as a victim of sexual exploitation, emerges in the 2000s as the chaste keeper of Kyoto’s classical artistic traditions. No longer viewed as a toy for men’s amusement, she serves as catalyst for women’s consumer fun. This change inspires stories of ordinary girls—and even one (fictional) boy—striving to embody the maiko ideal, engaging in masquerades that highlight questions of personal choice, gender performance, and national identity.

How did this change in perspective happen? I did not find any one event or policy that created this change. Certainly, Japan’s growing affluence and rise in girls’ education in the postwar contributed. Near the end of the 1990s, controversies over the sexual exploitation of girls in pornography, crimes against the “comfort women” brutally enslaved by Imperial Japan, and panic over girls’ alleged “compensated dating” shaped the cultural moment. In contrast, the maiko emerges as innocent and sheltered. Narratives of the 2000s emphasize her agency–she chose this apprenticeship–and elders’ dedication to her training in etiquette and arts. This emphasis on artistry idealized the maiko as the quintessential Kyoto girl, a picture of poise and refinement. Popular literature, drama, and manga show how ordinary teens struggle to realize this pose, often feeling as though in a masquerade. Interestingly, most narratives emphasize stories of maiko, including relatively few about geisha. This allows the innocent apprentice to remain the focus of attention, relegating the geisha, an independent, self-supporting, unmarried woman, to the margins. Maiko Masquerade shows the romance of girlhood in millennial Japan and the discomfort surrounding independent career women.

I drew on my students’ insights into representation and their imaginative work to create teaching materials for Maiko Masquerade. Twenty years later, my book finally provides an answer to my students’ questions about geisha in modern life. I hope readers enjoy learning the fascinating insights this investigation revealed.