“We didn’t get our forty acres and a mule, but we got you, C[hocolate] C[ity]!”— George Clinton on the title track of Parliament Funkadelic’s 1975 Chocolate City album

“We didn’t get our forty acres and a mule, but we got you, C[hocolate] C[ity]!”— George Clinton on the title track of Parliament Funkadelic’s 1975 Chocolate City album

Black History Month provides an opportunity to reflect on the numerous events, social movements, and figures that have spurned societal change.

It also allows us to consider how far U.S. society has genuinely come in reflecting these values as well as what still needs to be done.

Over the past few decades, from Central District Seattle to Harlem to Holly Springs, Black people have built a dynamic network of cities and towns where Black culture is maintained, created, and defended. But imagine—what if current maps of Black life are wrong?

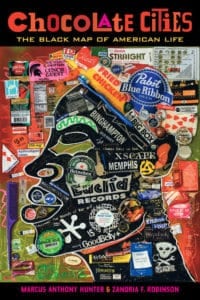

In Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life, authors Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson trace the Black American experience of race, place, and liberation, mapping it from Emancipation to now. In their Preface, they share why this journey is still required. Using the Parliament Funkadelic’s 1975 Chocolate City album as a jumping off point, they note:

Rather than wait for unfulfilled political promises, Black Americans were occupying urban and previously White space in massive numbers, their movement and increasing political power embodied on the track by multiple yet complementary melodies. Bass and piano take turns keeping the beat and beginning new melodies, saxophones speak, a synthesizer marks a new era, and a steady high hat ensures the funk stays in rhythm. The Parliament, its own kind of funky democratic government, chants “gainin’ on ya!” as Clinton announces the cities that Black Americans have turned or will soon turn into “CC’s”: Newark, Gary, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and New York. Parliament’s “Mothership Connection” public-service announcement is broadcast live from the capitol, in the capital of chocolate cities, Washington, DC, where “they still call it the White House, but that’s a temporary condition.”

Spurred on by postwar suburbanization, by 1975 the chocolate city and its concomitant “vanilla suburbs” were a familiar racialized organization of space and place. The triumphant takeover tenor of Chocolate City may seem paradoxical in retrospect, as Black people inherited neglected space, were systematically denied resources afforded to Whites, and were entering an era of mass incarceration. Still, for Parliament, like for many other Black Americans, chocolate cities were a form of reparations and were and had been an opportunity to make something out of nothing. For generations these chocolate cities—Black neighborhoods, places on the other side of the tracks, the bottoms—had been the primary locations of the freedom struggle, the sights and sounds of Black art and Black oppression, and the container for the combined ingredients of pain, play, pleasure, and protest that comprise the Black experience.

Four decades after Chocolate City, including eight years of the first African American president, what is the status of Clinton’s Afrofuturist vision of the chocolate city? Did Barack Obama turn the White House Black? Which cities became chocolate cities? How have the connections between cities expanded and shifted? And what does it mean when the CC capital is no longer, in fact, a CC? How have Black Americans mobilized space, place, geography, and movement to resist and repair the conditions in which they find themselves?

Inspired by a collection of Black intellectuals, adventurers, explorers, culture producers, and everyday folk, the goal of this book is to expand and extend the idea of the chocolate city, tracing it from its antebellum origins to the Black Lives Matter era. We use and pluralize the funk-inflected sociopolitical concept, henceforth chocolate cities, to disrupt and replace existing language often used to describe and analyze Black American life. Though always present in Black artistic and intellectual endeavors, the idea of chocolate cities and this book are uniquely linked to the story of how we came to meet, know, understand, and care for one another.

Read more from Marcus and Zandria on their thoughts on why Los Angeles is still part of The South and how Black lives are affected by current policies today. And see both Marcus and Zandria on March 24th at Crosstown Concourse at Chocolate Cities: A Symposium, co-presented by the Center for Southern Literary Arts and Africana Studies at Rhodes College.