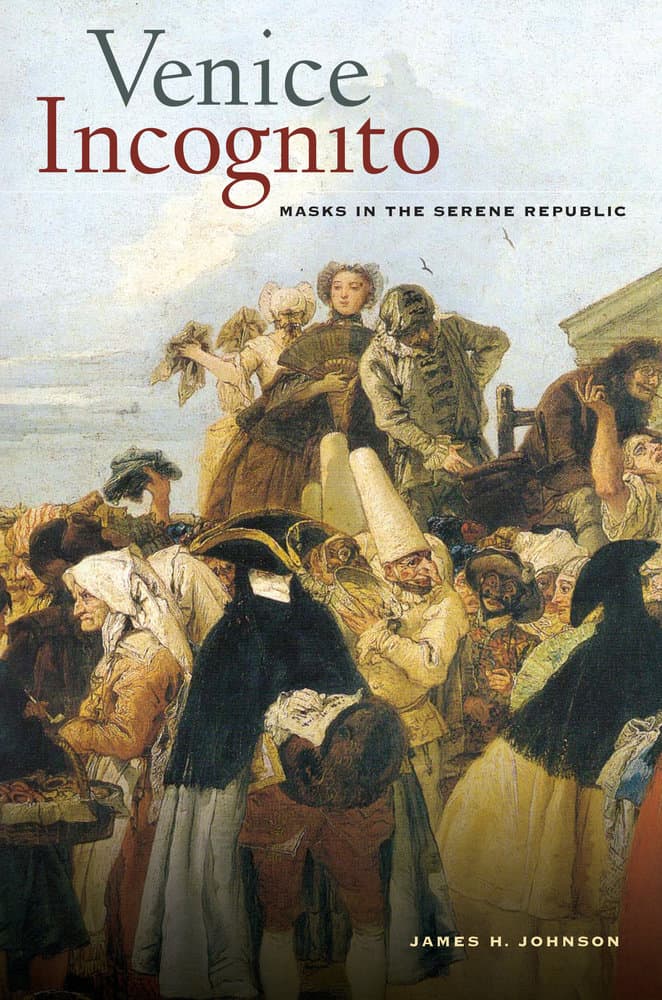

By James H. Johnson, author of Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic

“Man is least himself when he speaks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.” Oscar Wilde’s quip is a fair description of how many view the mask: as freedom from constraints, a liberating truth-teller, the way to show who we really are. I had Wilde’s notion in mind when I first started thinking about writing a book on masks. At least in the prosperous parts of the world, masks affirm what social mobility, abundant consumer choice, and technology make possible: perpetual reinvention of the self.

Writing about masks in Venice, I wa s powerfully reminded just how recent the freedom to reinvent ourselves actually is. What did masks mean for people living in societies where you were born into a role that determined your fate? Where charting your own path was the exception and changing your identity was unheard of?

s powerfully reminded just how recent the freedom to reinvent ourselves actually is. What did masks mean for people living in societies where you were born into a role that determined your fate? Where charting your own path was the exception and changing your identity was unheard of?

Venice was one of the most rigidly hierarchical states in Europe, and in the eighteenth-century it was awash in masks. We think of it as the capital of carnival—rightly so, with travelers from across the continent and around the world converging for its celebrations. But Venetians also wore masks for six months out of the year, outside of the carnival season and for occasions that were far from festive. They wore masks at formal receptions and state ceremonies, in public theaters and cafes, in the sprawling gambling hall, and, despite prohibitions, sometimes in church.

The Venetian mask—an unadorned piece of white waxed cardboard that extended to just below the nose—was an accepted article of clothing for over a century. Most of the time, it wasn’t meant to be secretive, mysterious, or provocative. Instead it was a way for this vastly unequal population living in close quarters to go about their daily business without the complicating protocols of rank and deference. Masks preserved a psychological space where physical distance was lacking. Of course they could hide identities, but their usefulness didn’t depend on anonymity. Much of the time these neighbors recognized one another. They preserved and protected social roles by temporarily suspending them. For these reasons, they were conservative.

Since finishing Venice Incognito, I’ve been thinking about how other societies have seen in masks a version of their own ideals, fears, and illusions. For later writers and artists who probed the unconscious, for instance, the mask was an object of doom and fascination, a portal into the unknowable depths of the psyche. “Your soul is a choice landscape,” the poet Paul Verlaine wrote, “where masks and Bergamasks pass entrancing, / Playing lutes and dancing, slightly / Sad in their strange costumes.”

Today’s masks more often send us online than toward the murky landscape within. Our digital selves couple limitless masking with unprecedented visibility. The personal information we willingly share—a continuous account of what we’re buying, reading, eating, watching, and listening to—stands alongside a wider record of choices and habits that grows with every click. The audience for our digital identities is friends, family, and numberless strangers. It also includes the sophisticated software of marketers and political campaigns, with potential uses by employers, insurance carriers, and domestic surveillance bureaus.

Online visibility transforms the self into a fragmented, quantified, and unmoored series of data points. It may be that the thing we find so appealing about Oscar Wilde’s promise—that masks reveal the truth of the self—has begun to recede. The risk is that the self becomes its mask.

James H. Johnson is a cultural historian who writes and teaches on modern and early modern Europe at Boston University. His research includes eighteenth- and nineteenth-century France, the history of Venice, and music history. His book Listening in Paris: A Cultural History received the American Historical Association’s 1995 Herbert Baxter Adams Award and the American Philosophical Society’s Jacques Barzun Prize while Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic received the American Historical Association’s 2011 George L. Mosse Award and Oscar Kenshur Book Prize.

H. Johnson is a cultural historian who writes and teaches on modern and early modern Europe at Boston University. His research includes eighteenth- and nineteenth-century France, the history of Venice, and music history. His book Listening in Paris: A Cultural History received the American Historical Association’s 1995 Herbert Baxter Adams Award and the American Philosophical Society’s Jacques Barzun Prize while Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic received the American Historical Association’s 2011 George L. Mosse Award and Oscar Kenshur Book Prize.

Venice Incognito is now available in paperback. James H. Johnson will be in New Orleans, speaking at the New Orleans Museum of Art, March 24 at 6pm and at Octavia Books, March 25 at 6pm.