This post is part of a blog series leading up to the American Musicological Society annual conference taking place in Vancouver, Canada from November 3–6. Please visit our booth if you are attending, and otherwise stay tuned for more content related to our Music books and journals programs.

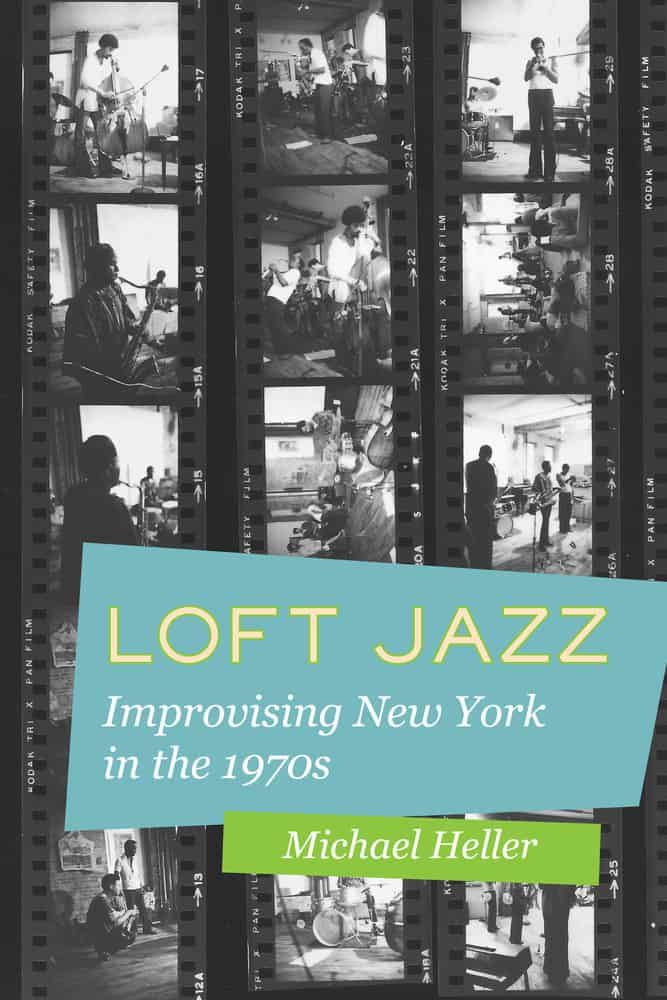

by Michael Heller, author of Loft Jazz: Improvising New York in the 1970s

Like so many others, I graduated college without a plan. The only thing I knew was that I wanted to work in music, and I somehow stumbled into a job with New York’s Vision Festival – one of the premier showcases of the jazz avant-garde. It was a small operation, with just three of us huddled in a tiny office in the East Village apartment of Patricia and William Parker. Patricia—a dancer and choreographer—was the organization’s executive director. In ten years, she had built the festival up from a tiny event run on $5,000 and elbow grease into a major event attracting international audiences and securing funding from top arts organizations. The work also put me in close contact with a close-knit community of avant-garde improvisers, based primarily around lower Manhattan. When I would ask about their influences, one topic kept cropping up over and over again: the New York loft scene of the 1970s.

What were the jazz lofts? In a nutshell, the lofts were a collection of venues organized by musicians inside of mostly vacant industrial buildings in lower Manhattan. Musicians often lived in the spaces as well, blurring the line between public and private spheres. The jazz history books that I had read so dutifully as an undergrad had scarcely a mention of them, although they cropped up occasionally in artist bios (“So and so began their career performing in lofts before moving on to…”). Yet for a generation of New York artists, the vibrancy of the loft era remained a powerful source of inspiration. It was influential not only due to the music that was created, but also for the empowering value it placed upon artist-organized production strategies—strategies that continue to animate projects like Vision up to the present day. It was those conversations in Patricia’s apartment that fueled my initial fascination, ultimately resulting in this book.

Loft Jazz: Improvising New York in the 1970s makes no attempt to offer a comprehensive history of the scene. Instead, it works to unravel various threads of meaning that surrounded loft practices. This includes extended explorations of terms like “freedom” and “community,” ideals that crop up so frequently in jazz discourse but that can mean very different things in different contexts. It also considers the ramifications of private archiving among musicians, particularly in relation to a wave of affordable, consumer-grade recording equipment that came on the market in the 1960s. For a scene that produced fewer commercial records than earlier periods in jazz, these private archives become the linchpin for reconstructing the histories of local musical networks, even in the jazz mecca of New York City.

Over the course of my research, I would also learn that not everything about the lofts could be spun into a tidy romance. The spaces were as controversial as they were celebrated, beloved by some and abhorred by others. Perhaps nothing attracted more ire than the very phrase “loft jazz,” which opponents claimed was never a coherent style. Worse yet, some argued that the phrase glorified the meager settings in which innovative African American artists were forced to perform. These arguments are part of the story as well, and play a major role in the complex and conflicted legacies surrounding the period. But to those who remembered them fondly, the power of the lofts lie in the excitement surrounding a scene that teemed with artistic opportunity. Where music could be experienced every night on every block, and opening a venue could be as simple as opening your living room.

Michael C. Heller is an ethnomusicologist, music historian, and Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Pittsburgh.

Michael C. Heller is an ethnomusicologist, music historian, and Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Pittsburgh.