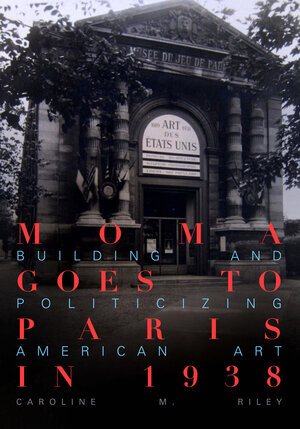

Three Centuries of American Art in 1938 was the Museum of Modern Art’s first international exhibition. With over 750 artworks on view in Paris ranging from seventeenth-century colonial portraits to Mickey Mouse and spanning architecture, film, folk art, painting, prints, and sculpture, it was the most comprehensive display of American art to date in Europe and an important contributor to the internationalization of American art. MoMA Goes to Paris in 1938 explores how, at a time when the concept of artworks as “masterpieces” was very much up for debate, the exhibition expressed a vision of American art and culture that was not only an art historical endeavor but also a formulation of national identity. Caroline M. Riley demonstrates in what ways, at the brink of international war in the politically turbulent 1930s, MoMA collaborated with the US Department of State for the first time to deploy works of art as diplomatic agents.

Caroline M. Riley is Research Associate in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of California, Davis. A curator and academic, she is a historian of American visual culture in a global context.

How did you find Three Centuries of American Art, MoMA’s first international exhibition?

Displayed in Paris in 1938, Three Centuries of American Art has a clear paradox in its title. How could a country founded in 1776 have three centuries of culture only 162 years after its founding? I discovered the exhibition explored many key art-historical questions—politics, the role of technology, the combination of low and high art, and the convoluted roles of collectors, curators, diplomats, insurance companies, shippers, and the press in the making of American art history. In the face of World War II, the exhibition still happened. Traveling throughout the United States, Great Britain, and France, I sorted the thousands of records that surrounded the over 750 artworks on view. The archives were deep and rich and often slightly breathtaking. In the records, diplomats and curators questioned the relative danger of the Nazis versus the safety of the artworks.

The book would not have been possible without Dorothy Dudley, the 1930s MoMA registrar, who made duplicates of the many letters, bureaucratic forms, and internal memos that ensured I could track the shifting mindset of an exhibition nearly ninety years later. Having worked as an eighteenth-century specialist, I am used to an inventory, a cache of letters, and silence from women and people of color. I knew the archives were a gift and would allow for an immersive analysis.

What motivated you to write the book?

As a curator and an academic, I look to museums as the site for my thinking about American art during the pivotal 1930s period. My deep appreciation of museums led to my desire to write about the importance of curators in art criticism and the power of exhibitions in shifting how the public understands their place in American culture. Viewing art can be transformative and exhibitions can transport each of us to a different place, a different experience, or a different time. In the choice of artworks and thematic decisions, MoMA curators guide us through their vision of American culture. It is an intimate exchange of ideas through the display of artworks that is built on trust in the curator’s voice. Done improperly, curators can misinterpret culture, misinterpret artworks, and exclude people’s experiences. Most Americans are unlikely to read art historical texts. Instead, exhibitions become the touchstones of their understanding of their place in American culture.

As Americanists working on the 1930s, we often focus on what was happening within the nation’s geographical borders and as a consequence of the Great Depression. I am fascinated by this work, but I sought to reframe American art by traveling to Europe and extending the 1930s to the interwar period, a strategy more often seen in European art history as the method for dividing time. This proved useful for the book. It is hard to acknowledge the newness of American art history but my research on Three Centuries demonstrated how messy our collective art history is as a discipline and historiography.

What does Three Centuries of American Art show us about American art and culture at that time?

Exhibitions are wonderful objects to research because they capture the complexity of the culture created during the period in which they were made. However, it is difficult to easily summarize exhibitions because they are vast, dense, and long-lasting—what I call their “exhibitionary life cycle.” Scholars often mention exhibitions in relation to an artist, art movement, or geographical location but fail to provide a clear understanding of how the curator interpreted the artwork in the exhibition. To interested French audiences, Three Centuries of American Art presented a modern, socioeconomically and geographically complex United States that emphasized mass culture, industrialization, capitalism, and the changing American landscape. With artworks dating back to 1609, MoMA folded Indigenous and colonial histories into the definition of the United States while largely ignoring native and enslaved cultures. Further, more than three hundred artworks in the exhibition represented the American landscape in its diversity: the spread of farms, the congestion of cities, the scale of factories, antiquated American defenses, and the porous oceans. I hope this book demonstrates the richness of exhibitions not only for museum studies but more broadly for art history.

What’s the main message you hope readers will take away from the book?

MoMA Goes to Paris in 1938 is larger than a single exhibition. It is a strategy of integrating exhibitions as a vital measure and voice, a system of inventorying and advocating, in art history. It is also a method of inquiry that could open art history up to new questions and audiences at a time when the discipline must adapt.

These decisions are intentional on my part. Curators hoped that the exhibition would influence contemporary artists. They sent invitations to at least ninety-one well-known graphic designers, painters, sculptors, and theorists, a “who’s who” of European art that included Hans Arp, George Braque, A. M. Cassandre, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Wassily Kandinsky, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Nikolaus Pevsner, Gertrude Stein, and Tristan Tzara. Slowly, as the exhibition was delayed in 1932, then 1937, before its eventual display in 1938, its political message became more overt. American and French diplomats worked to support the display as a manifestation of American democracy on view in France.

Indeed, Three Centuries of American Art proved to be the first time the US Government employed a MoMA exhibition as a form of soft power. In addition to building the legacy of Alfred Barr Jr., A. Conger Goodyear, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, my research uncovered the many hands that sustained Three Centuries of American Art. In particular,two extraordinary women stood out: Dorthey Dudley, MoMA’s head of registration, and Sarah Newmeyer, head of MoMA’s publicity department. These two women created the bureaucracy and infrastructure that ensured the exhibition could go on view in the face of World War II and spread the word of the exhibition in hundreds of articles that traveled around the world from Australia to Germany.

What’s something surprising you learned while writing the book?

There were so many surprises, and I will leave most of them to the reader to discover. In general, I was struck by the necessary interpretive flexibility of artworks for MoMA curators and for the essential diplomatic work that the exhibition performed. For example, when I began, I never would have guessed that there were at least 26 Communist artists in the exhibition—a number that did not yet appear to bother MoMA administrators or the approximately 30 diplomats invited to the exhibition preview. This would change during World War II.

Lastly, I hope the readers can sense the joy I had in writing the book and the marvel I felt in my discoveries. Art history is struggling as a profession right now, but art historians are vital to our understanding of culture. We are a relatively small group of people versed in the visual complexity of the world around us and able to share that knowledge with others. As the world becomes more digital and more visual, we are a vital linchpin, demonstrating the complicated legacy of seemingly new images. I hope readers can also sense the stakes in the Three Centuries of American Art’s display, the risks that MoMA and other museums took, and the desperation of diplomats to try anything to strengthen the relationship between France and the United States.

Visit our CAA 2023 virtual exhibit page to get 40% off the book for a limited time