Although the 2021 American Studies Association meeting is now virtual, it was originally set to take place in Puerto Rico with the theme “Creativity within Revolt.” According to ASA, “revolt expresses a will toward collective being that radically challenges, displaces, and potentially abolishes life-altering, people-and-planet destroying relations of dominance.” Read more about the meeting theme here.

To highlight the conference themes, we reached out to three UCP authors to discuss their recent books on Puerto Rico, and how their work ties into the concept of revolt.

Catalina M. de Onís is Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Colorado Denver. She is the author of the new book, Energy Islands: Metaphors of Power, Extractivism, and Justice in Puerto Rico and coauthor of the book “¡Ustedes tienen que limpiar las cenizas e irse de Puerto Rico para siempre!”: La lucha por la justicia ambiental, climática y energética como trasfondo del verano de Revolución Boricua 2019. She researches and teaches environmental and energy communication, Latina/o/x communication, Puerto Rican studies, de/coloniality, applied communication, and ethnographic methods.

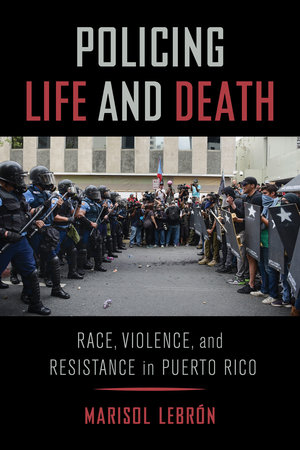

Marisol LeBrón is an Associate Professor of Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz and author of the book, Policing Life and Death: Race, Violence, and Resistance in Puerto Rico and Against Muerto Rico: Lessons from the Verano Boricua. An interdisciplinary scholar, Dr. LeBrón’s research and teaching focus on social inequality, policing, violence, and protest.

Ismael García Colón is Professor of Anthropology at the College of Staten Island and The Graduate Center, City University of New York. He is a historical and political anthropologist with interests in political economy, oral history, migration, Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, farm labor, race and citizenship, U.S. empire, and U.S ethnic and

racial histories. His research experiences include documenting Latinxs in the NYC labor movement, and conducting ethnographic research on landless workers, migrant farmworkers, colonial state formation, and land distribution programs in Puerto Rico. García Colón is the author of Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on US Farms, winner of the 2020 Frank Bonilla Book Award from the Puerto Rican Studies Association, and Land Reform in Puerto Rico: Modernizing the Colonial State. His publications have also appeared in Latin American Perspectives, CENTRO Journal, American Ethnologist, Latino Studies, and Dialectical Anthropology.

How does your book display “creativity within revolt” among the people of Puerto Rico?

de Onís: Energy Islands: Metaphors of Power, Extractivism, and Justice in Puerto Rico draws on historical and ethnographic research to document how grassroots actors and activists confront environmental racism and energy injustices in the Jobos Bay region of southeastern Puerto Rico. Community members draw on numerous organizing strategies and tactics to refuse the ongoing pollution and poisoning of human and more-than-human bodies in the environments they call home. As racial capitalism, neoliberalism, and colonialism threaten their survival, the individuals and groups featured in this book strive to live otherwise via apoyo mutuo (mutual support) networks rooted in autogestión (self-reliance). These collective creative energies build connections of care among community neighbors in the form of local multimedia projects, food cultivation and meal preparing and sharing, solar community education and installations, house rebuilding and repairs, and much more. In tandem with these communal efforts, the activists and actors who animate the pages of Energy Islands collectively work to uproot oppressive systems and structures that suffocate their rural coastline communities, evincing the urgency of radically transforming power in its many forms.

LeBrón: Policing Life and Death explores how Puerto Ricans have challenged logics and practices of punitive governance that promote harm and premature death in the archipelago. I show how punitive governance weighs most heavily on populations who are already marginalized because of race, class, sexuality, and spatial location. These punitive logics and practices are embedded in a range of social relations and institutions beyond those that we might traditionally associate with the punitive state, such as police, prisons, detention centers, and courts. For example, Puerto Ricans themselves participate in “informal” strategies of policing one another that deepen the reach of the punitive state into the realms of the interpersonal and everyday. As a result, Puerto Ricans have deployed creative, and sometimes surprising, strategies of resistance against the punitive violence that undergirds the colonial capitalist state. Cultural production, like underground rap music, zines, and even social media campaigns, allows Puerto Ricans to push back against the notion that certain populations, namely low-income, Black Puerto Ricans, were to blame for crime and that harm and death were acceptable forms of punishment for criminalized populations. These forms of cultural production open up an alternative archive of crime, punishment, and resistance in Puerto Rico that shows criminalized people as creative and agentive, rather than mere victims of the punitive state, as they worked to craft a more just future.

García-Colón: Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire helps us understand farmworkers’ strategies of contention. By examining the history of U.S. agrarian labor, racial relations, colonialism, and immigration, my book details how agricultural labor camps and fields in the United States are sites that emerge from a carceral logic, reinforced through labor and deportation policies without obliterating human agency entirely. The government of Puerto Rico could have developed a sustainable and diverse agricultural production instead of sending the unemployed more than 1,500 miles away to work on U.S. farms. Rethinking alternative futures for migrant farmworkers is an attempt to liberate the colonized and the dispossessed, as well as food consumers.

What is the main thing you hope readers take away from your book?

de Onís: I hope readers will think about and critically respond to oppressive discourses, metaphors, and narratives that conceptualize Puerto Rico’s experiences following Hurricanes Irma and María as a “natural” disaster that paints residents as “helpless” victims. Four years after these storms of climate chaos made landfall in September 2017, it remains crucial to challenge trauma-centric framings of experiences. These framings ignore the ways that the grassroots actors and activists in Puerto Rico who are most negatively impacted by energy and climate injustices create their own present and future, despite serious obstacles. The suffering experienced by residents is a result of systems—and the rhetorical materials that uphold them—that devalue and mark Puerto Rican life as exploitable and expendable. Hopefully, Energy Islands encourages readers to contemplate carefully and act ethically toward supporting communication practices that powerfully reshape struggles in Puerto Rico and beyond to advance self-determined energy justice.

LeBrón: Punitive logics and structures are not the only or most appropriate way of responding to crisis. I argue that punitive logics and practices expanded and consolidated as a result of colonial and capitalist crisis in contemporary Puerto Rico. While feelings of social insecurity increased among many segments of Puerto Rican society as a result economic collapse and the growth of a violent informal economy, more police and harsher punishment were not the only way the state could have responded. I show how, after three decades of harmful tough on crime policies, activists are working to come up with non-punitive, community-based solutions to violence.

One of the most creative and exciting examples was Taller Salud’s Acuerdo de Paz program, which worked to decenter policing as the only response to gang violence in the low-income, Black community of Loíza. Rather than just calling the police, Acuerdo de Paz staffers recognized the humanity of the young men caught up in the streets and worked to remind them and others that their lives and futures mattered. Staffers, many of whom had experienced criminalization or otherwise had credibility in the community, regularly mediated conflicts and engaged with the young men in the gangs in order to get to the bottom of what was causing the violence. As a program administered by a feminist public health organization, one of the most surprising and successful strategies they used to reduce violence was to work with the young men to change their attitudes around masculinity. Acuerdo de Paz staff worked to reorient their ideas of masculinity away from accessing power through violence and control and towards community care and responsibility. In many ways, the program has had better results and garnered much more community trust that the police have, given their racist and brutal treatment of residents. Unfortunately, Acuerdo de Paz is underfunded and has been impacted by the ongoing debt crisis.

The reality is that struggle and social change are messy, complicated, uneasy, and often contradictory – and our texts should reflect and embrace that. When we try to craft these neat narratives, we often leave out the incredibly creative ways that people resist and navigate structures of power and inequality.

Marisol LeBrón

García-Colón: I argue that Puerto Ricans are more than U.S. citizens—they are also colonial subjects. U.S. immigration policies are central to understanding Puerto Rican migrant farm labor, which has fluctuated as a result of guestworker programs and deportation practices. Federal immigration policies shape their migration even though they are U.S. citizens. U.S. colonialism allowed the government of Puerto Rico to play a strong role in the formation of Puerto Rican communities on the mainland and to manage migration. It allowed the insertion of Puerto Rican officials into the agencies of the federal government and the establishment of migration offices in the United States, and not due to a transnational state.

The problems of Puerto Ricans in the US labor market are not those of incorporation or lack of assimilation. Rather, inequalities and power have shaped their migration. Immigration policies are part of how states organize these inequalities, shaping not only the lives of immigrants but also the lives of citizens and colonial subjects. Despite discrimination and other enduring challenges, migration remains an alternative for many Puerto Ricans to survive in a colonial regime devastated by economic crisis, government debt and corruption, policies of austerity, and climate change and disasters. The status of Puerto Ricans as U.S. colonial subjects reveals the complexity of the definitions and practices of who is a citizen and who is an immigrant in the twenty-first-century United States.

How can American Studies scholars embrace creativity within revolt in the way they approach their work?

de Onís: While there are substantial pressures to publish for academic audiences in peer-reviewed, “top-tier” journals, I have tried to communicate my research to wider publics to create space for alternative intellectual projects. For example, the documentary El poder del pueblo: una lucha colectiva por la vida y el medioambiente (The Power of the People: A Collective Struggle for Life and the Environment) is a community-produced documentary that I contributed to while conducting research for and writing Energy Islands. Similarly, I coauthored a bilingual children’s book, La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí/Environmental Justice Is for You and Me, which seeks to reach younger audiences in the Spanish and English languages. Both creative works translate and advocate for self-determined environmental, climate, and energy justice by consensually centering and amplifying the perspectives of the most marginalized residents in Puerto Rico, who describe their experiences on and in their own terms. For more information about these projects, please visit: https://elpoderdelpueblo.com and https://catalinadeonis.com/environmental-justice-is-for-you-and-me-a-bilingual-childrens-book/.

LeBrón: One of the ways I tried to approach this, which hopefully will resonate with others, is through refusing the lure of the “neat package.” There is a lot of pressure, especially for early career scholars, to demonstrate a mastery over their topic and to act like they have all the answers. This results in a lot of people leaving interesting and important parts of their research on the cutting room floor because it doesn’t “fit” or it complicates the coherence of the narrative they’re crafting. The best American Studies work I’ve read doesn’t necessarily leave me feeling like everything was wrapped up neatly at the end. The reality is that struggle and social change are messy, complicated, uneasy, and often contradictory – and our texts should reflect and embrace that. When we try to craft these neat narratives, we often leave out the incredibly creative ways that people resist and navigate structures of power and inequality.

García-Colón: American Studies scholars should continue looking at how people imagine and practice rebellion, focusing not only on their discursive, artistic, and cultural understandings, but also on their strategies to earn a living. The discipline must examine subjectivities in relation to racial, gender, and sexual formations without disregarding their relation to social class. We also need to continue paying attention to how working-class subjectivities emerge, disappear, or change. Scholars can contribute to build counter-hegemonic projects and a new common sense based on justice and solidarity.