By Judith Byfield, co-editor of Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century

A few weeks ago, we were subjected to yet another infamous statement by Donald Trump. His statements—Nigerians live in huts; all Haitians have AIDS; El Salvador, Haiti and African nations are s***hole countries—reflect a long pattern of racist assumptions that are embedded in American culture. While it may be reassuring to think that Donald Trump speaks only for himself, the reality is that he speaks for many people who think African societies lack great thinkers, ancient civilizations, history and religion. Africans somehow managed to exist outside of world history stuck in tradition until slavery and colonialism dragged them into the modern era. Moreover, the political and economic crises that exist in many African countries are the result of their inability to learn how to become Western democracies.

A few weeks ago, we were subjected to yet another infamous statement by Donald Trump. His statements—Nigerians live in huts; all Haitians have AIDS; El Salvador, Haiti and African nations are s***hole countries—reflect a long pattern of racist assumptions that are embedded in American culture. While it may be reassuring to think that Donald Trump speaks only for himself, the reality is that he speaks for many people who think African societies lack great thinkers, ancient civilizations, history and religion. Africans somehow managed to exist outside of world history stuck in tradition until slavery and colonialism dragged them into the modern era. Moreover, the political and economic crises that exist in many African countries are the result of their inability to learn how to become Western democracies.

These ideas and assumptions have histories to them, and they continue to do important work. Notions of African racial and cultural inferiority, for example, helped bolster and sustain the institutions of racial slavery in the Americas. They helped slave owners and their descendants to cast themselves as benevolent masters instead of a class of people who crafted systems of sadistic violence in the pursuit of wealth. These assumptions also placed a cloak of invisibility around the human and ecological costs of producing gold and diamonds for fashion statements and ivory for leisure pursuits (piano keys, pool balls). Equally important, they enable Donald Trump and many others to believe that any positive developments in Africa are due to the influence of Euro-Americans and all negative developments are the result of African actions only. Finally, racist assumptions allow Trump & Co. to believe that African immigrants bring no value to the American project. In their calculation, human value correlates to race and only whites, i.e. Norwegians, bring value.

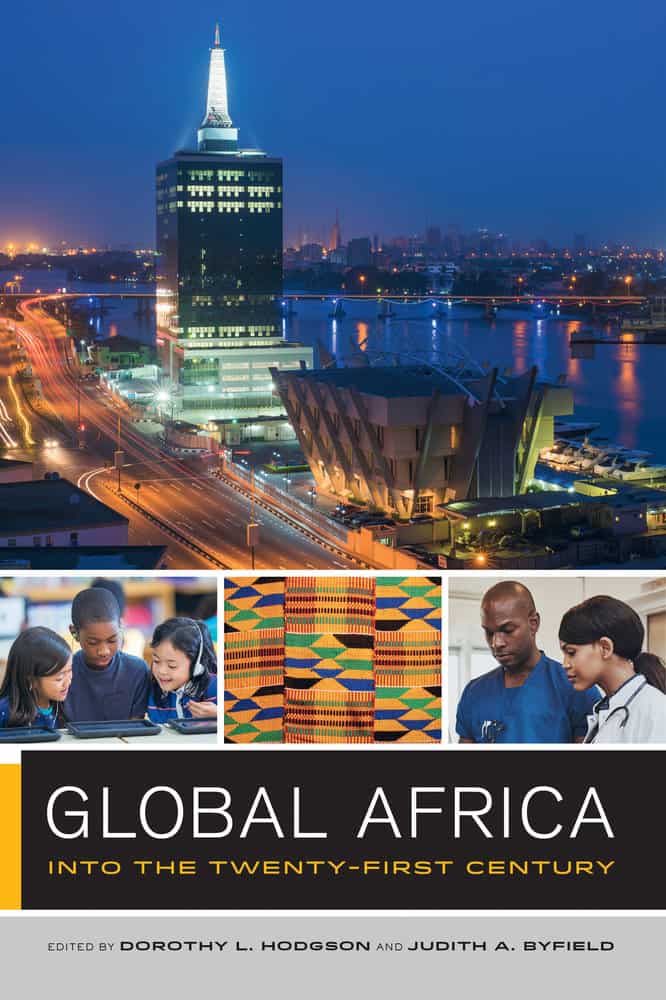

Those assumptions are challenges for those of us who teach about Africa for we have to help our students recognize racist assumptions and the multiple ways in which they are re-invented for successive generations while teaching them about a continent that is dynamic and central to world history. The volume, Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century, can be a very helpful tool in the struggle to combat racism and ignorance. The cover alone begins the task for it shows an image of Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, at night. This image contrasts with the one in Donald Trump’s mind.

Contributions

The first piece, a profile of Ibn Khaldun and last selection, a photo-essay on a utopian village in Ethiopia, highlight intellectual contributions to the social sciences and the promise of gender equality (1.1 – “Ibn Khaldun: The Father of the Social Sciences” by Oludamini Ogunnaike ; 5.7 – “Awra Amba: A Model “Utopian” Community in Ethiopia” by Salem Mekuria). Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, as Chambi Chachage shows, was also an important thinker on the world stage (2.3 – “Mwalimu Nyerere as a Global Conscience”). Nyerere provided an important critique of the world economy, its interdependence, and the privileges some countries enjoyed at the expense of African nations among others. The economic crises affecting many African countries was not the result of their failure to learn or corruption, it also resulted from policies promoted by the West during the colonial and post-colonial periods.

Politics and Economics

Corruption is often offered as the only explanation for issues on the continent, however, most of us hold a simplistic view of how it works and the parties involved. Masimba Tafirenyika explores the significant role multinational corporations play in exporting US$50 billion every year from the continent to Europe and the US through illicit business transactions (2.6 – “Commerce, Crime, and Corruption: Illicit Financial Flows from Africa”). Africa also exports resources critical to the digital economy and James H. Smith sheds light on the human and ecological costs of acquiring these minerals (4.5 – “What’s in Your Cell Phone?”). The confluence of political and economic decisions in Africa and abroad have made it difficult for many people to create the future they desire for themselves and their children on the continent. Therefore, many leave their homes hoping to secure the future they desire abroad.

Migration

African migration has a long history. Men, women and children have left for many reasons and under different circumstances. Some left as part of forced migrations to the Americas and India as Frank Trey Proctor and Renu Modi demonstrate in their respective chapters (1.5 – “From the Land of Angola”: Slavery, Marriage, and African Diasporic Identities in Mexico city before 1650”; 1.7 “Africans in India, Past and Present”). Modi notes that many Africans also travelled to India as students or medical tourists. Religion informed migration as well. Heidi Haugen shares stories of Nigerians who travel to China to bring the Christian gospel while Cheikh Babou introduces us to Senegalese imams who ventured to the U.S. to share the teachings of Islam (3.3 – “Sending Forth the Best: African Missions in China”; 5.5 “Globalizing African Islam from Below: West African Sufi Masters in the United States”). Mukoma Wa Ngugi helps us understand the complexity of exile for Kenyan author, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Britain and the U.S. provided refuge to Ngũgĩ after he was arrested by the Kenya government for criticizing inequality and injustice in the country (3.5 – “The African Literary Tradition: Interview with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o”). A prolific writer and thinker, Ngũgĩ matches the educational profile of so many African migrants in the United States. The Migration Policy Institute found that sub-Saharan immigrants have a “higher educational attainment compared to the overall foreign-and native born populations.”

Racism

Donald Trump’s racism and the power he now holds to put it into policy threatens scholars and activists around the world who, like Ngũgĩ, speak truth to the powerful in their homelands. His racism hides the many ways in which the U.S. is implicated in the political and economic turmoil that feed migration from Africa, El Salvador and Haiti. It also masks the benefits the U.S. accrues from the capital exported from these countries as well as the educational attainment, skills and sheer determination of immigrants who now call America home. Saddest of all, the racism practiced and promoted by Donald Trump and the greed that accompanies it threatens America itself. Understanding Africa’s past and present may help Americans better grasp what is at stake under this president for the indices he uses to designate these countries s***holes are already in play here.

For further information, see the Census re: Foreign-Born Population from Africa and the Education of US-based African Immigrants.

Judith A. Byfield is Associate Professor of History and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Cornell University. She is the co-editor of Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century, along with Dorothy L. Hodgson, Professor of Anthropology and Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs in the Graduate School – New Brunswick at Rutgers University.

Judith A. Byfield is Associate Professor of History and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Cornell University. She is the co-editor of Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century, along with Dorothy L. Hodgson, Professor of Anthropology and Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs in the Graduate School – New Brunswick at Rutgers University.