This interview was originally featured in Loyola University of Chicago’s Department of History blog, and has been reposted here with their kind permission in conjunction with the North American Conference on British Studies Annual Meeting in Denver, CO Nov. 3-5.

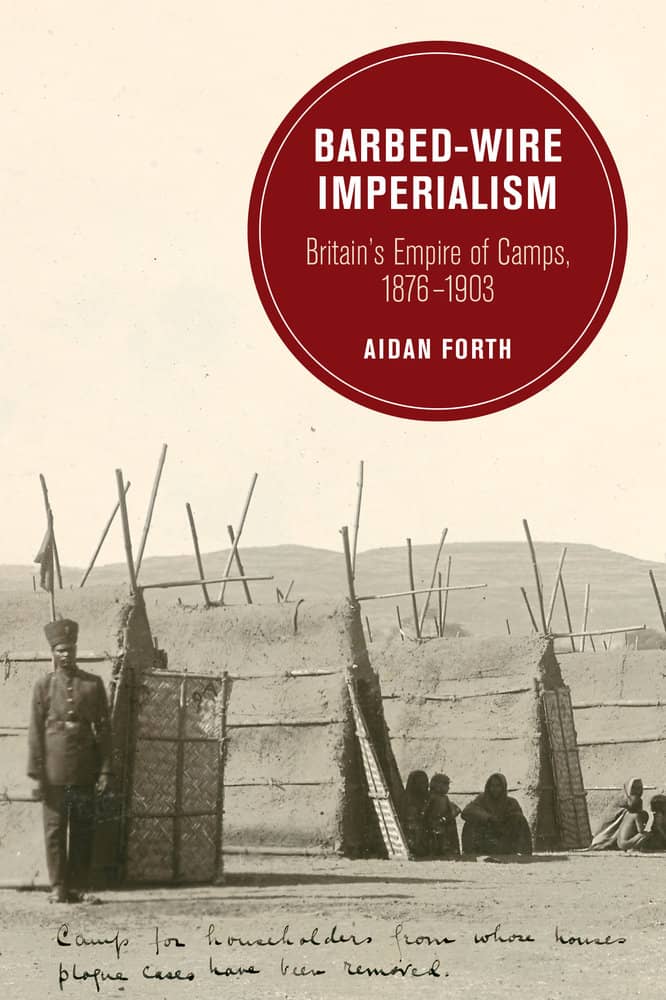

Aidan Forth is an assistant professor of history at Loyola, where he teaches courses on modern British history, imperialism, and transnational urban history. Dr. Forth recently returned from a semester abroad as a visiting professor with the University Studies Abroad Consortium (USAC) at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic. His first book, Barbed-Wire Imperialism: Britain’s Empire of Camps, 1876-1903, was published this fall. Loyola Public Media Assistant Meagan McChesney asked him a few questions about his experience in Prague, the recent release of his book, and the courses he is teaching at Loyola this year.

Q: Congratulations on the publication of your first book! In the book, you examine the world’s first “concentration camps.” How did your interest in this important topic develop?

A: Camps have long fascinated me as emblems of the twentieth century and of everything that went wrong—violence, prejudice, and even genocide—in the two world wars. When I learned the first “concentration camps” were erected not in Nazi Germany but in the British Empire during the South African War (1899-1902), I realized there was a hidden history of camps that could tell us much about ourselves. That a regime as racist and violent as Hitler’s Third Reich would concentrate racial minorities and other social “undesirables” in barbed-wire pens is hardly surprising. That a liberal democracy like Britain, which valued (or claimed to value) human rights, individual freedom, and the rule of law, first “invented” the concentration camp is an advent that demands more explanation. In the concentration camps of the British Empire we are confronted with the dark side of liberalism: we see what happens when a liberal and imperial power confronts populations deemed dangerous, “uncivilized,” and supposedly unworthy of exercising freedom. We are also provided with the opening chapter of a larger, global narrative of mass incarceration that encompasses the “concentration camps” of the United States and other liberal democracies, from the Japanese “internment” camps of WWII to Guantanamo Bay, which Amnesty International recently deemed the “Gulag of our times.” Moreover, the attitudes and anxieties that governed British colonial camps live on today in the detention of refugees and migrants in vast barbed-wire enclosures across the global south and on the frontiers of Europe and America.

Q: You recently returned from teaching a summer course entitled “Concentration Camps: Mass Confinement from the Age of Empires to the European Migrant Crisis” at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic. How did the content of this course align with your interests?

A: Teaching and research are always interconnected. My class on concentration camps broadens the scope of my own research, but has also helped me carve out my own scholarly contribution, as an historian of Britain, in a field dominated by histories of totalitarian violence. The class examines British concentration camps in the South African War as well as earlier iterations of forced encampment in colonial India, before charting the evolving form and function of concentration camps over the course of the twentieth century, from Nazi Konzentrationslager to the Soviet Gulag and beyond: “camps de regroupement” in Algeria, “strategic hamlets” in Vietnam, and “new villages” in Malaya all feature in class, as do native reservations, slave plantations, leper colonies, and Australia’s controversial offshore detention facilities on Nauru and Christmas Island. Students compare and contrast camps in their diverse and evolving iterations while tracing their changing form and function over time. Memoirs, diaries, and the accounts of humanitarian reformers offer insight into the lived experience of inmates, from Alexander Solzhenitsyn to unnamed children in Namibia. So too did a site visit to the Terezin concentration camp north of Prague and the town of Lidice, which was liquidated by the Nazis. Further, the course considers the politics of naming and the continuing power of the “camp,” as both a symbol and a warning, in the world today. Was Pope Francis right to describe a refugee facility in Greece as a “concentration camp”? Was Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s own use of the term “concentration camp” to describe his “tent city” in the Arizona desert appropriate? Like my book, the goal of the course is to tell a global history via the microcosm of the camp and to approach an infamous institution from new and provocative angles. Teaching abroad was a fabulous, stimulating and rewarding experience and I’d highly recommend Loyola students to explore USAC many exciting exchange opportunities, both in Prague and all across the world!

Q: What courses are you teaching at Loyola this year? What do you hope your students will take away from each of those courses?

A: I’m currently teaching History 102: Western Ideas and Institutions since the 17th century and History 325: Great Britain since 1760. In their own ways, both courses grapple with a central paradox of the modern age: humanity, in the twentieth century, conducted total war, genocide, and nuclear holocaust, but at the very same time, it made remarkable strides in building mass democracies and embracing open, pluralistic societies. Apart from the basic skills that all good history fosters—critical reading, writing, and analytical thinking—my courses are about people. Why do we suffer, and why do we inflict suffering? To this end, I’ll be teaching a new version of the course I taught in Prague—History 300E Concentration Camps: A Global History of Mass Confinement—and I hope to see some new and familiar faces in the classroom!

Q: Both writing and teaching difficult histories come with their own challenges. How did you address those challenges throughout both experiences?

A: History demands both critical analysis and human empathy. Striking a balance between the two is especially difficult—and especially important—with a subject as politically charged as concentration camps. The Holocaust, in particular, pushes social science to its limits: how can we remain analytically detached in the face of an event that many consider sacrosanct? Historiographical disputes can seem hollow when faced with six million corpses. In such cases, reverence must accompany rational explanation. The same is true for British concentration camps during the South African War, which were by no means as violent as their Nazi counterparts, but which have lived on in public memory, often in troubling ways. As I found out during my time in South Africa, camps are a hot-button entrée into discussions about race, colonialism, and post-apartheid reconciliation; they require special sensitivity. In the classroom, meanwhile, my course on camps often tackles disturbing material. Alain Resnais’s graphic Holocaust film Night and Fog, in particular, prompts raw emotions. I’ve also had Loyola students personally describe the trauma their families have faced moving through refugee facilities, transit camps, and migrant detention centers. Ultimately, however, knowledge is power, and my overarching goal is to prompt action and understanding. Both my writing and teaching examine the conspicuous differences and essential similarities between camps in a wide variety of contexts—and both emphasize that camps, in many guises, continue to populate the world today. By spotlighting contemporary injustices and their historical genealogies, I want my students to feel empowered to address them.

Aidan Forth is Assistant Professor of British imperial history at Loyola University Chicago. His book, Barbed-Wire Imperialism: Britain’s Empire of Camps, 1876-1903, is part of the Berkeley Series in British Studies.