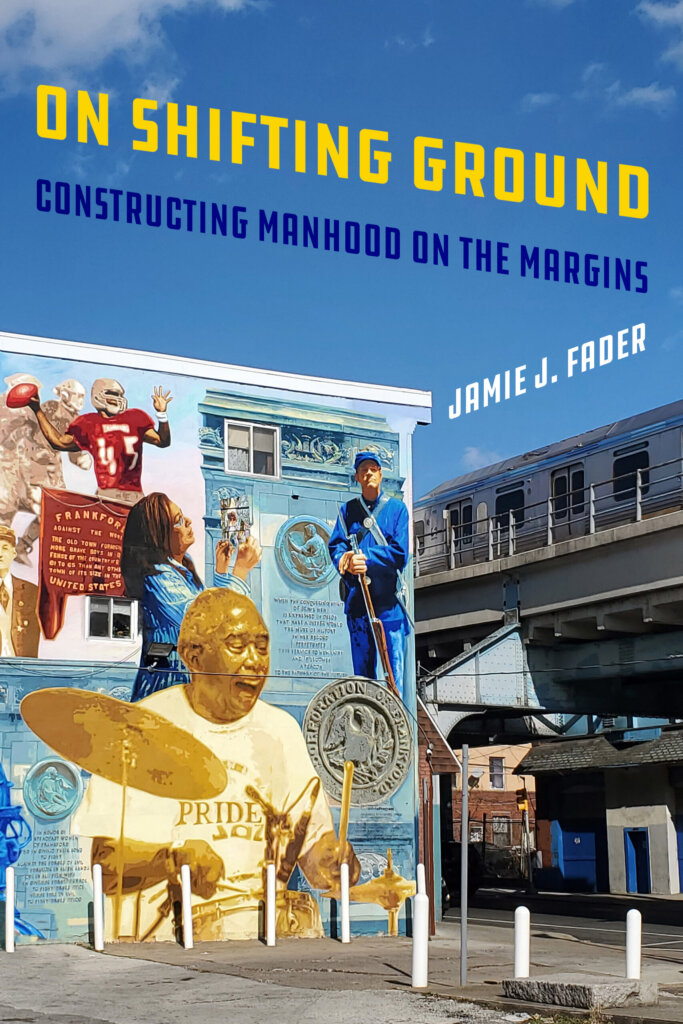

By Jamie J. Fader, author of On Shifting Ground: Constructing Manhood on the Margins

Although “the end of men” is hardly imminent, it is important to consider how mass incarceration and declining labor market participation have deepened intragender social inequalities, creating a large and growing class of men without stable employment prospects and who are vulnerable to system contact. In 2014, I began attending community meetings in a high-crime, heavily surveilled community Philadelphia to study how millennial men (born 1981-1996) navigated new and shifting definitions of manhood. Yet, when my research team arrived in Frankford, we couldn’t find any men under forty years old, even when visiting typically male spaces such as basketball courts, barber shops, gyms, and bars. We tapped our connections with the women and elders of the community to assemble a sample of 45 men without college degrees. Through extensive life history interviews, we learned more about the social dynamics behind the missing men.

Almost all of the men of color interviewed in Frankford reported that the constant presence of the police drove them indoors in order to avoid the unpredictable drama that could result from something as simple as walking to the store or shaking someone’s hand. Their direct and vicarious experiences of racial profiling, arrest, violence by other men or the police, and false charges led them to engage in “network avoidance,” a deliberate restriction of social ties that they feared may bring trouble. This adaptation often meant a complete lack of engagement in their community, in civic or service organizations, and even in getting to know their neighbors.

Network avoidance is a raced and gendered adaptation to the expansion of the criminal legal apparatus and the unpredictable nature of men’s interactions with its agents and enforcers. It effectively erases young men of color from the public sphere in the same way that incarceration removes them from their communities, with considerable costs to the men themselves and their neighborhood. However, despite their fears of arrest, incarceration or violent death, the Frankford men expressed a desire to give back to the community and to be connected to others through generative activities. Many had dreams of being employed in caring or helping professions. They were concerned with being remembered as good and generous people and very often served as informal mentors to youth or did outreach with homeless individuals or those living with addictions. Their attempts to create new definitions of manhood through caring about and for others suggests the need for policy makers to reconnect young men to their communities as paid mentors, violence interrupters, or credible messengers.

This post is part of our #ASA2023 blog series. Visit our virtual ASA 2023 website and find out how to get 40% off our books.