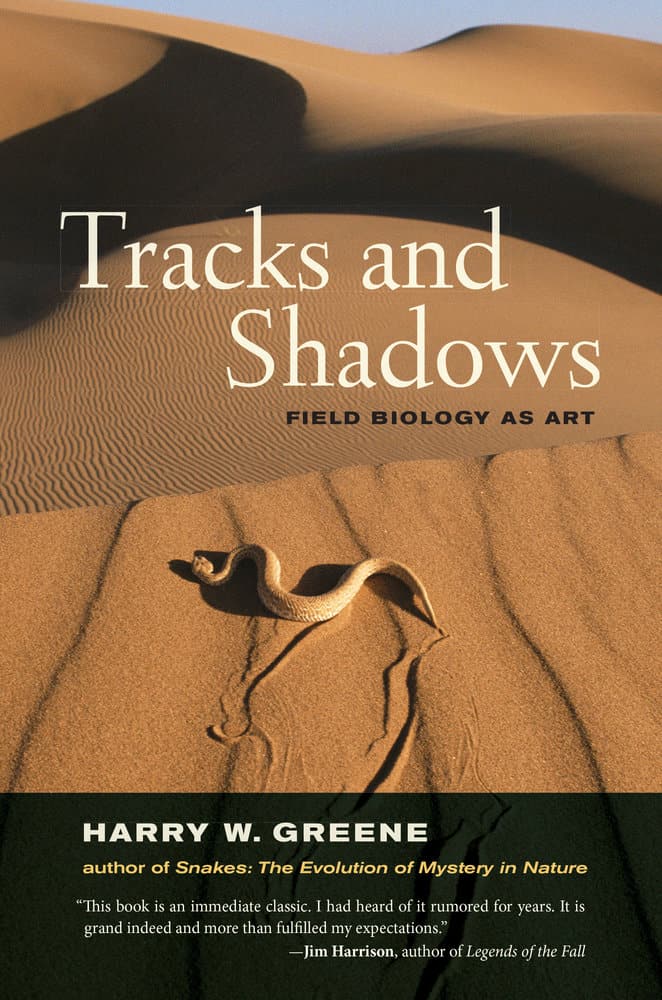

by Harry W. Greene, author of Tracks and Shadows: Field Biology as Art

This guest post is published to coincide with the Ecological Society of America conference in Fort Lauderdale. Check back every day this week for new posts through the end of the conference on August 12th.

I conceived of Tracks and Shadows: Field Biology as Art in the 1980s, while awaiting tenure at Berkeley, then realized that art, let alone life and death, were beyond my youthful grasp. Three decades later it pushed past teenage nerdiness, past five years as a medic, even beyond fascination with snakes. Now, after four decades of teaching, nature-loving creds secure, I’m above all curious about humans as spectators of, versus participants in, wildness. And as explained in my little memoir, time on a Texas ranch, home to about two hundred vertebrate species, has been pivotal. Out on the Double Helix, I’m born again as a deer and feral pig predator, all the while observing Longhorns, cattle shaped by half a millennium of selection in that semiarid landscape.

I conceived of Tracks and Shadows: Field Biology as Art in the 1980s, while awaiting tenure at Berkeley, then realized that art, let alone life and death, were beyond my youthful grasp. Three decades later it pushed past teenage nerdiness, past five years as a medic, even beyond fascination with snakes. Now, after four decades of teaching, nature-loving creds secure, I’m above all curious about humans as spectators of, versus participants in, wildness. And as explained in my little memoir, time on a Texas ranch, home to about two hundred vertebrate species, has been pivotal. Out on the Double Helix, I’m born again as a deer and feral pig predator, all the while observing Longhorns, cattle shaped by half a millennium of selection in that semiarid landscape.

Countless pages have parsed “wilderness” and “wildness,” from postmodernist claims of Western conceit to Wilderness Act definitions and declarations of inherent values. In brief, nature-lovers often conceptualize wilderness as untrammeled (“leave only footprints, take only pictures”), wild places and creatures as uncontrolled by us (“self-willed”). These formulations risk veering into nonsense and elitism, but more problematically, even as we bemoan disjunction from nature—Friends of the Earth’s motto was once “not man apart”—our reigning notions of wildness minimize human involvement.

Instead, as I argued in a recent Mind and Nature essay, the key ingredients of wildness should be organisms that have historically shaped ecosystem function, especially large herbivores and predators.

By situating us as spectators rather than participants, “untrammeled” ignores that ecology signifies, rather than “loving nature,” influential, multi-directional relationships among organisms, including us. By precluding significant roles for humans, “no-control” plays into denial that we are part of nature—packaging hides from us the origin of meat, bears still shit in the woods but we shouldn’t, and so forth. Moreover, big and dangerous organisms remind us that wildness means participating in predator-prey relationships, nutrient cycling, and other ecosystem processes. Wild thus implies being responsibly more part of nature rather than less, engaged in ecological relationships instead of just pondering them—seeing where food comes from and waste goes, acknowledging, at least from the sidelines, a risk of our own demise from predation.

As for more personal rewards, I’m healthier, more attentive, and immeasurably happier for time spent outdoors, especially when I’m more participant than spectator. Wild places, especially those with big herbivores and predators, have humbled me in the face of grandeur and shrunk my selfish concerns to manageable size. Their inhabitants have drawn me into other worlds, thereby enlarging my own.

Harry W. Greene is the Stephen Weiss Presidential Fellow and Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University and a recipient of the E.O. Wilson Award from the American Society of Naturalists. His book Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature (UC Press), won a PEN Literary Award and was a New York Times Notable Book.