1,412 Results

UC Press February Award Winners

Mar 09 2026

UC Press is proud to publish award-winning authors and books across many disciplines. Below are our February 2026 award winners. Please join us in celebrating these scholars by sharing the news!

Read More

How Brazilian Cinema Captured the Moment: A Q&A with Gerd Gemünden

Mar 09 2026

Winner of two Golden Globes, "The Secret Agent" has been nominated for four Academy Awards. The film's critical success underscores the special moment Brazilian cinema is currently enjoying.

Read More

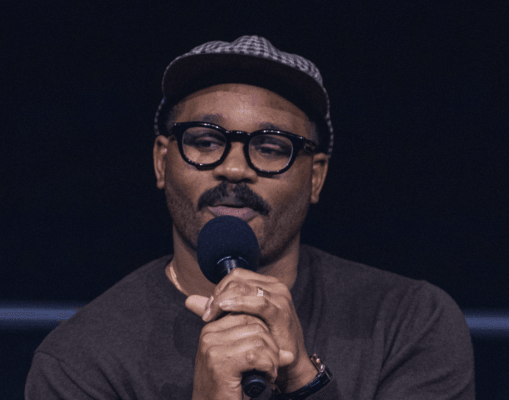

Whether of Not "Sinners" Wins the Oscar, Ryan Coogler’s Genre-Bending Film Signals a New Era for Original Cinema

Mar 06 2026

A Q&A with "Film Quarterly" contributor Anthony Michael D’Agostino

Read More

"I hope 'One Battle After Another' wins a million awards": A Q&A with Peter Coviello

Feb 26 2026

For me, Anderson is a filmmaker who read a book about state terror and counterfascist mobilization and metabolized Pynchon’s "Vineland" into the unlikeliest of things: a movie, a mass-cultural product that wants to think clearly and hard about the here-and-now-ness of an American fascism.

Read More

Webinar: Navigating Publishing and Academia as a FirstGen Scholar

Feb 19 2026

Hear career and publishing insights from FirstGen authors and UC Press staff at our upcoming FirstGen webinar!

Read More

JAMS Author Interviews: Ruthie Abeliovich, Daniela Smolov Levy, Joanne Cormac, and Benjamin Ory

Feb 18 2026

"Journal of the American Musicological Society" editor Jake Johnson conducts video interviews with the contributors to the journal's Summer 2025 issue.

Read More

UC Press January Award Winners

Feb 17 2026

UC Press is proud to publish award-winning authors and books across many disciplines. Below are our January 2026 award winners. Please join us in celebrating these scholars by sharing the news!

Read More

Excerpt from Keren Rosa Hammerschlag's "The Chosen Race"

Feb 13 2026

An exclusive look at Keren Rosa Hammerschlag's THE CHOSEN RACE with an intro by the author.

Read More

Q&A with Sérgio B. Martins, author of "Borderless Painting as Borderless Art"

Feb 13 2026

Author Sérgio B. Martins explains what the trajectory of Antonio Diaz's life and artwork reveals about the history of avant-gardism.

Read More

Erosive Forms and a Climate of Violence in the Work of Juan Rulfo: A Q&A with Mark Anderson

Feb 11 2026

Mark Anderson talks about his ecocritical analysis of Mexican writer Juan Rulfo.

Read More