1,407 Results

Webinar: Navigating Publishing and Academia as a FirstGen Scholar

Feb 19 2026

Hear career and publishing insights from FirstGen authors and UC Press staff at our upcoming FirstGen webinar!

Read More

JAMS Author Interviews: Ruthie Abeliovich, Daniela Smolov Levy, Joanne Cormac, and Benjamin Ory

Feb 18 2026

"Journal of the American Musicological Society" editor Jake Johnson conducts video interviews with the contributors to the journal's Summer 2025 issue.

Read More

Q&A with Sérgio B. Martins, author of "Borderless Painting as Borderless Art"

Feb 13 2026

Author Sérgio B. Martins explains what the trajectory of Antonio Diaz's life and artwork reveals about the history of avant-gardism.

Read More

Excerpt from Keren Rosa Hammerschlag's "The Chosen Race"

Feb 13 2026

An exclusive look at Keren Rosa Hammerschlag's THE CHOSEN RACE with an intro by the author.

Read More

Erosive Forms and a Climate of Violence in the Work of Juan Rulfo: A Q&A with Mark Anderson

Feb 11 2026

Mark Anderson talks about his ecocritical analysis of Mexican writer Juan Rulfo.

Read More

How Transpacific Contemporary Art Reveals Imperialism’s Role in the Global Rise of Fascism

Feb 11 2026

Author Namiko Junimoto on how the work of transpacific contemporary artists exposes colonial trauma and the rise of aspirational fascism.

Read More

News: Recent UC Press Book Signings

Feb 09 2026

We're thrilled to announce a selection of our latest book signings!

Read More

Recovering Women’s Film History in the Archive

Feb 04 2026

How author Aurore Spiers recovered women's hidden labor in the film history archives and their contributions to French cinema.

Read More

Thirty Years of “Pacific Historical Review”: New Articles on Gray Wolves, US-Pacific Expansion, Iberian Transpacific Trade

Feb 03 2026

Preview the new Winter 2026 issue of "Pacific Historical Review."

Read More

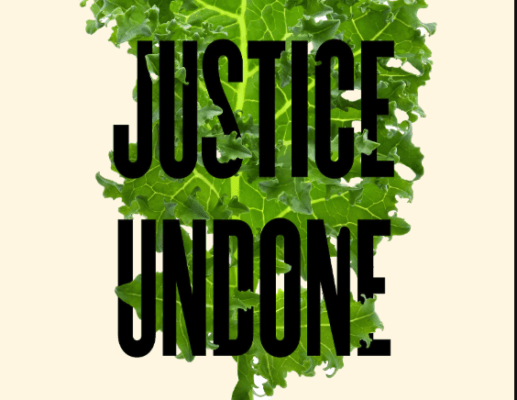

What Food Justice Gets Wrong and How to Build a Better Movement

Feb 03 2026

Author Hanna Garth set out to document a radical, grassroots movement of residents fighting for food justice — but encountered a very different reality.

Read More