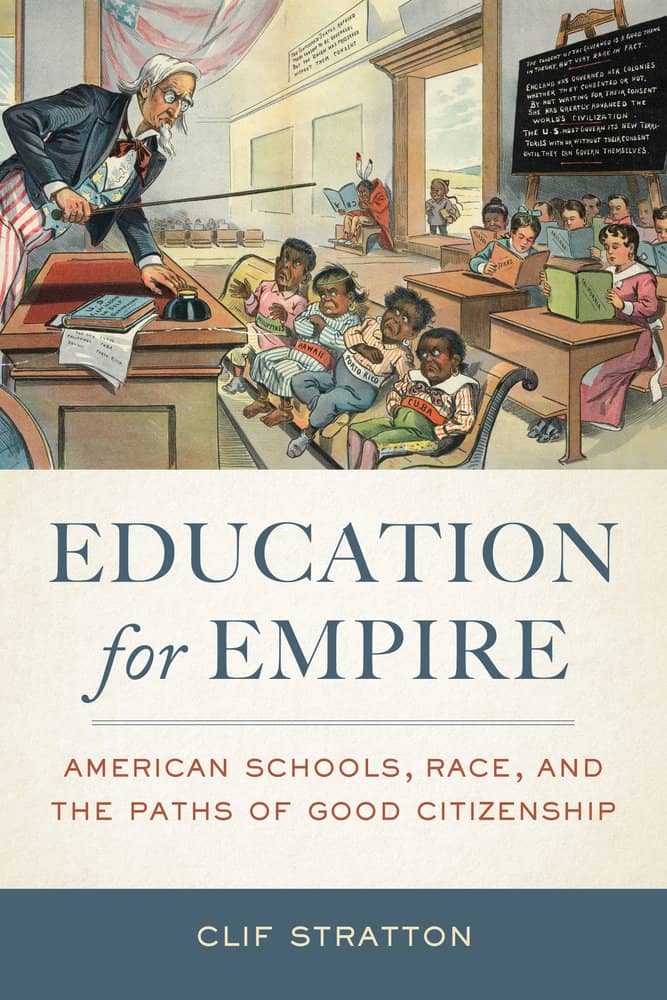

by Clif Stratton, author of Education for Empire: American Schools, Race, and the Paths of Good Citizenship

This guest post is part of a series published in conjunction with the meeting of the Organization of American Historians in New Orleans. The theme of this year’s conference is “Circulation,” which characterizes many of the subjects historians study, whether migrations, pilgrimages, economies, networks, ideas, culture, conflicts, plagues or demography. #OAH17

While Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is likely in for a long fight should she seriously push for painful “school choice” programs, President Trump’s deportation policies are having an immediate and detrimental impact on U.S. students and schools.

While Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is likely in for a long fight should she seriously push for painful “school choice” programs, President Trump’s deportation policies are having an immediate and detrimental impact on U.S. students and schools.

In late February, the Bay Area’s Mercury News reported a forty percent drop in the number of college financial aid applications from undocumented students. California’s Dream Act allows undocumented students brought to the United States as children to access financial aid and in-state tuition. But Donald Trump’s “military operation” aimed at ramping up deportations has many high school and college students wary of providing identifying information to government authorities.

Two weeks later, ICE arrested Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez, an undocumented father of four U.S. citizens while driving his daughter Fatima to school in northeast Los Angeles. The family was less than two blocks from Fatima’s school, which signaled, according to reports, that ICE may discard its long-standing policy not to conduct enforcement raids at hospitals, churches, schools, and other “sensitive sites.”

Meanwhile, in the Aloha state, public school social studies (social studies!) teacher John Sullivan used his work email to announce: “If [students] are in the U.S. illegally, I won’t teach them.” His email was in response to that of school counselor who cited national statistics concerning an increase in school absences over deportation fears.

Historians of American education will find these intersections of immigration policy and public education horrific yet unsurprising. As unions and lawmakers in California and other western states moved to bar first Chinese then Japanese migrants from entering the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century, school administrators actively participated in the xenophobic hysteria by segregating citizens and non-citizens of Asian descent in inferior schools. Some school officials openly advocated deportation.

In New York and other eastern industrial cities where southern and eastern European immigrants settled for jobs, housing, and education, school board members and administrators first pressed for rapid assimilation—“100 percent Americanism,” as they called it. When school officials perceived those efforts to fail, many threw their support behind the National Origins Act of 1924 which effectively barred from entry those of alleged racial inferiority or Bolshevistic proclivity (the Bolshevik was the era’s “really bad dude”).

What has certainly changed from a century ago—John Sullivan aside—is the position of educators. Top officials for both the University of California and California State University systems have assured students that they will not comply with any ICE requests for student information.

Chicago Public Schools likewise refused: “To be very clear, CPS does not provide assistance to [ICE] in the enforcement of federal civil immigration law,” a memo stated in late February.

Meanwhile, in the Red State South, the largest university in the University System of Georgia—Georgia State University—began admitting students regardless of their immigration status this semester.

And on O’ahu, where a little over a century ago territorial officials ran a reform school for native Hawaiians and immigrants that functioned an awful lot like a prison, John Sullivan faces disciplinary action for his email and the cold shoulder of the state teachers’ association.

Educators are clearly uninterested in returning to the days in which their predecessors actively colluded with the xenophobes in union halls, state houses, or Washington, D.C. They have repeatedly attested that all children deserve a public education, regardless of immigration status. In doing so, they serve as vital bulwarks against the politics of division and those that seek to deepen, not close, the education gap in the United States. This colleague, for one, commends them.

Clif Stratton is Clinical Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Director of the Roots of Contemporary Issues program at Washington State University. He is the 2014 recipient of the American Historical Association’s Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award.

Clif Stratton is Clinical Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Director of the Roots of Contemporary Issues program at Washington State University. He is the 2014 recipient of the American Historical Association’s Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award.