This guest post by Angela Sirna is based on her article “Tracing a Lineage of Social Reform Programs at Catoctin Mountain Park,” published in The Public Historian’s new special issue on the National Park Service Centennial. The full article appears in TPH 38.4 (November 2016), which can be purchased as a single issue. For more TPH content, become a subscriber via NCPH individual membership or ask your library to subscribe on your behalf.

This guest post by Angela Sirna is based on her article “Tracing a Lineage of Social Reform Programs at Catoctin Mountain Park,” published in The Public Historian’s new special issue on the National Park Service Centennial. The full article appears in TPH 38.4 (November 2016), which can be purchased as a single issue. For more TPH content, become a subscriber via NCPH individual membership or ask your library to subscribe on your behalf.

Sixty miles from Washington, DC, residents can escape the frenzy of the nation’s capital at Catoctin Mountain Park, a small National Park Service (NPS) unit located in western Maryland. There, visitors can hike and camp just mere yards away from the Presidential Retreat, where presidents from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Barack Obama have come to relax, strategize, or meet with guests (or where First Lady Michelle Obama can have an all-girls weekend with Beyonce). Visitors can enjoy the same scenery as world leaders, but they shouldn’t plan on catching a glimpse of “Camp Number 3”; it is not open to visitors. Catoctin Mountain Park’s special relationship to American presidential history, however, belies it’s own complicated past.

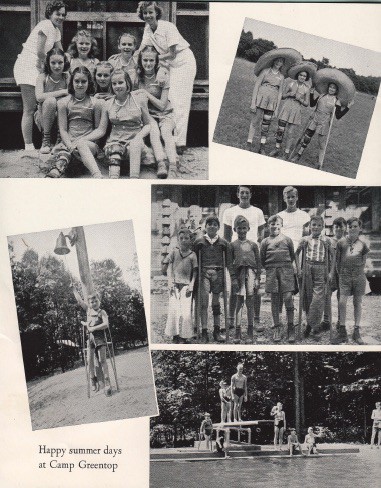

The federal government established the park during the New Deal through the Recreational Demonstration Area (RDA) program that purchased “submarginal” land (where production is carried at an economic loss) for recreation and conservation purposes, often displacing the local population. The NPS then utilized a succession of work programs to transform the mountain landscape into a park, including the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps (two New Deal programs), the Job Corps (a War on Poverty program), and Youth Conservation Corps (still used by the NPS today). New Deal park planners intended for the RDA to serve underprivileged youth from Washington, DC, and Baltimore. Camp Greentop has been home to the Maryland League for People with Disabilities for over seventy-five (mostly consecutive) years.

When we think about the NPS, we tend to think about it as a land conservation and historic preservation agency, or “bunnies and battlefields.” But, parks are about people, too. The NPS has a long history of incorporating social policy into its management practices. Such policies have created complicated legacies often fraught with institutional biases regarding race and class, such as the dislocation of families from park lands or segregation of park facilities. There is a growing body of literature in which scholars have examined some of these instances, but in my article, forthcoming in the November issue of The Public Historian (38.4), I use Catoctin Mountain Park as a case study to chart the evolution of social policy on a national park landscape. It places these changes in the larger context of economic, social, and land use policies throughout the twentieth century. These policies and programs often created complicated relationships between the park and certain groups.

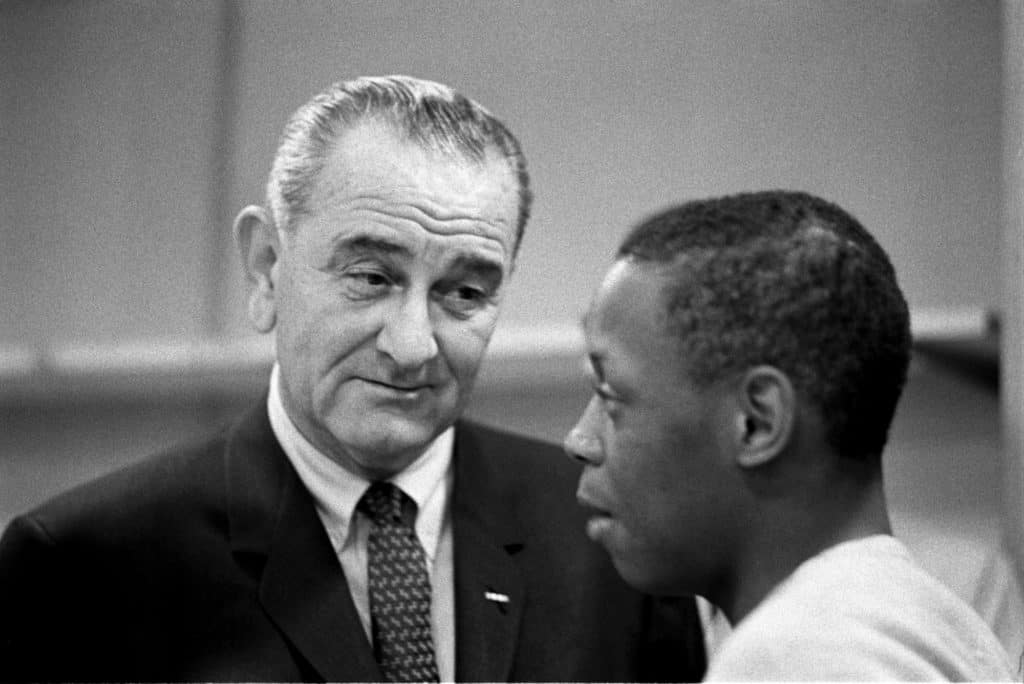

At Catoctin Mountain Park, for example, the creation of the RDA meant the dislocation of farm families from park lands, but the federal government offered little help in finding new places for them to live and farm. In fact, the NPS relied on the assumption that many would remain nearby and could be hired through work relief programs to help build the park. When the camps first opened to organizations serving underprivileged youth in Washington, DC and Baltimore, African Americans were excluded until World War II, when the NPS integrated parks to help bolster morale. And when President Lyndon B. Johnson announced a War on Poverty in 1964, Catoctin became the first site for a Job Corps Center, which brought young men from the lowest economic ladder to live, learn, and work in the park. The center was purposely integrated at a time when the rest of the country was grappling over race relations. The Catoctin Job Corps Center closed in 1969, but despite its short tenure, the center left an important physical imprint on the park’s landscape and provided valuable lessons to the agency as a whole.

Why should we care about this history in 2016? What does it mean for the park visitor or manager in this new century of stewardship? In the case of Catoctin Mountain Park, understanding the park’s history of social policy gives us a better appreciation of the park beyond its natural or recreational values. Acknowledging this past is critical for the NPS when reaching out to new groups. On a more general level, the NPS is involved in social policy now more than ever, through programs like the Urban Agenda and the variety of youth programming the agency employs. Oftentimes, old ideas are spun and rebranded as being new without careful consideration of how they worked in the past.

Angela Sirna is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at Middle Tennessee State University, where she recently completed an administrative history for Stones River National Battlefield. Her research interests include cultural landscapes and the history of the National Park Service. In particular, she has been examining the Job Corps program in national parks. Sirna has worked as a cultural resource specialist at C&O Canal National Historical Park and Catoctin Mountain Park. Read her full article at tph.ucpress.edu.