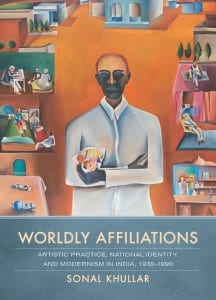

By Sonal Khullar, author of Worldly Affiliations

This guest post is published in advance of The World History Association conference in Savannah, Georgia. UC Press authors share their research and stories that reflect on this year’s two conference themes, Art in World History and Revolutions, Rebellions, and Revolts. Check back often for new posts.

The purpose of art, Amrita Sher-Gil wrote in 1936, was to “create the forms of the future.” Art was not limited by existing social and political conditions. Indeed it aimed to transform notions of nation and world. Unlike her counterparts in India, notably in Bengal, during this period, Sher-Gil did not believe there was an Eastern alternative to modernism, modernity, and the West. Indian artists would have to embrace oil painting, material conditions, and the historical present, and not look back to an idealized, spiritual, and premodern past. Sher-Gil’s model of making art and identity that resisted colonialist and nationalist norms proved influential in twentieth-century India.

Worldly Affiliations excavates a distinctive trajectory of modernism in the visual arts in India and emphasizes its cosmopolitan aims and achievements. It focuses on four artists —Sher-Gil, M.F. Husain, K.G. Subramanyan, and Bhupen Khakhar—who challenged the canons, disciplines, schools, and institutions of British colonialism and Indian nationalism. For these artists, cosmopolitanism was a critical response to colonialism, a way of asserting citizenship in national and international community that had been impossible under colonialism. This cosmopolitanism entailed a thoroughgoing investigation of categories such as East and West that propelled globalizing processes such as capitalism and colonialism. For the period I discuss in the book, the East was associated with the village, crafts, tradition, and nationalism, while the West was associated with the city, art, modernity, and colonialism. Artists challenged these associations, but the terms East and West remained active in various forms during the twentieth century.

Worldly Affiliations excavates a distinctive trajectory of modernism in the visual arts in India and emphasizes its cosmopolitan aims and achievements. It focuses on four artists —Sher-Gil, M.F. Husain, K.G. Subramanyan, and Bhupen Khakhar—who challenged the canons, disciplines, schools, and institutions of British colonialism and Indian nationalism. For these artists, cosmopolitanism was a critical response to colonialism, a way of asserting citizenship in national and international community that had been impossible under colonialism. This cosmopolitanism entailed a thoroughgoing investigation of categories such as East and West that propelled globalizing processes such as capitalism and colonialism. For the period I discuss in the book, the East was associated with the village, crafts, tradition, and nationalism, while the West was associated with the city, art, modernity, and colonialism. Artists challenged these associations, but the terms East and West remained active in various forms during the twentieth century.

Reflecting on the discipline of art history in the twentieth century, Subramanyan wrote: “Most histories of World Art emanating from European centres of culture present Europe as their main scene. . . . The arts of the rest of the world are side scenes that hook on to some point or other of this historical structure, or ladder of evolution: the arts of Africa, Pre-Columbian America, Oceania to the early stages; of Asia, to the middle (I still remember that when I visited the Edinburgh Museum in the mid-fifties all Asia was marked on a large cultural map displayed in its lobby as the Medieval world).” Subramanyan, like the other visual artists examined in Worldly Affiliations, deployed cosmopolitanism as a means to challenge logics that divided the world into East and West, medieval and modern, primitive and cultivated. This cosmopolitanism was a hallmark of modernism as it came to be practiced by artists in twentieth-century India, who explored worldly affiliations through unlikely—if ingenious—visual connections, synthetic gestures, and diverse archives of Eastern and Western cultural practice.

Sonal Khullar is Assistant Professor of South Asian art at the University of Washington. Her research interests include global histories of modern and contemporary art, feminist theory, and postcolonial studies. She is writing a book, The Art of Dislocation, on artistic collaboration as a critical response to globalization in South Asia since the 1990s.