This post is part of a blog series celebrating the College Art Association annual conference taking place in New York City from February 15–18. Please visit us at Booth 605 if you are attending, and otherwise stay tuned for more content related to our new and forthcoming Art books.

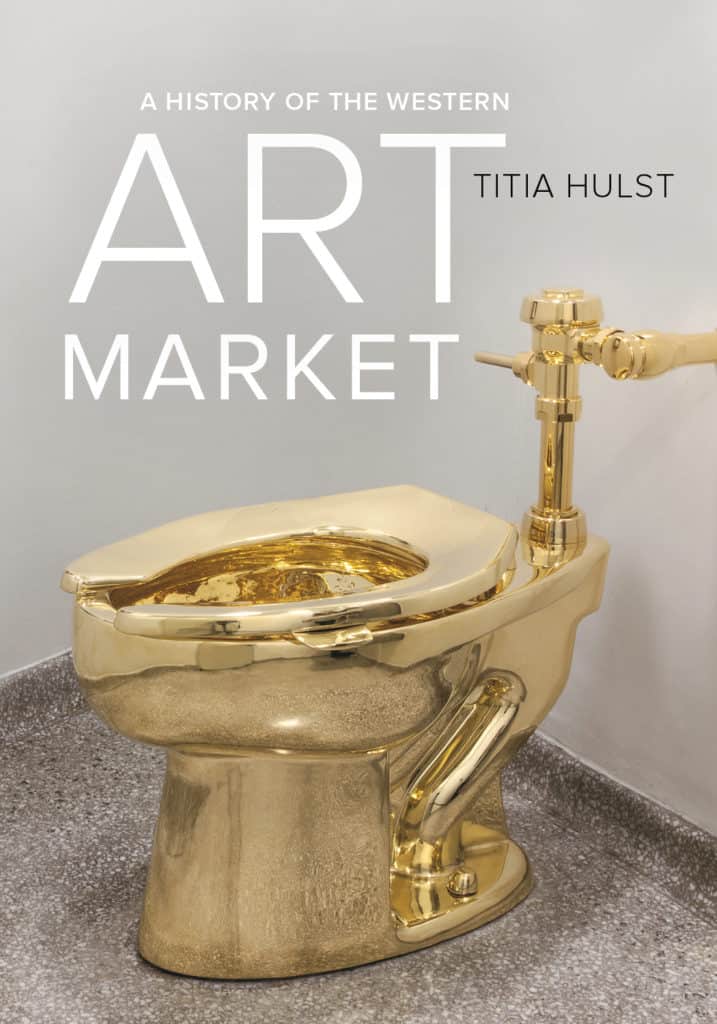

by Titia Hulst, author of A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets

Recent protests of two major contemporary artists in reaction to the election of President Trump made headline news. The decision by Christo, the artist known for his spectacular large-scale interventions in urban and rural settings, to cancel his latest project was hailed as the “Art World’s Biggest Protest Yet” by Randy Kennedy in the New York Times on January 25, 2017. Christo’s gesture of cancellation came on the heels of Richard Prince’s decision to disavow his portrait of Ivanka Trump, which was reported in the same paper on January 12. Kennedy’s presumption that Christo’s cancellation of his project was the more meaningful of the two appeared to be informed by the value that the artists had assigned to the works that were withdrawn ($15,000,000 vs. $36,000).

Prince had used Trump’s favorite communication tool—Twitter—to announce that his work, a large-scale canvas of a selfie Ivanka Trump had posted on Instagram, was no longer an authentic work by Richard Prince. “This is not my work. I did not make it. I deny. I denounce. This fake art,” he tweeted. The following day Prince clarified that his gesture was “Not a prank. It was sold to IvankaTrump & I was paid 36k on 11/14/2014. The money has been returned. SheNowOwnsAfake.” In an interview with the Times he added “I decided that the Trumps are not art.” Benjamin Sutton, writing for Hyperallergic, was quick to point out that Prince’s gesture could ultimately backfire, noting that “it’s unclear whether his public disowning of the work will negatively affect its worth and status as an authentic Richard Prince, or, on the contrary, it will add to its resale value.”

Not a prank. It was sold to IvankaTrump & I was paid 36k on 11/14/2014. The money has been returned. SheNowOwnsAfake. pic.twitter.com/zR2S6jZBA7

— Richard Prince (@RichardPrince4) January 12, 2017

Prince’s gesture goes to the heart of the question of what makes a work a work of art. The legendary dealer Leo Castelli, who had been instrumental in the transformation of the market for American art post-World War II, would have argued that an artist’s work does not exist as a work of art unless it has entered the market. He believed, in other words, that the market decides what constitutes a work of art and endows it with value – not the artist.

The problem Prince faced—the continuing existence of the Ivanka portrait—at first glance appeared to have been avoided by Christo. Implicit in the artist’s understated announcement “I no longer wish to wait on the outcome” of his Colorado project is the notion that his work would never be realized because Trump was elected. But the market has the power to compromise this gesture as well. Christo and his long-time partner Jeanne-Claude were financing the project partly through the sale of series of small works depicting the visual effects that they anticipated for the landscape intervention. One of these works, the collage Over the River. Project for the Payette River, Idaho from 1994, is currently for sale on the secondary market. Whether this and other related works will accrue additional value as a result of Christo’s gesture remains to be seen. I would not rule it out.

Titia Hulst is a modern and contemporary art historian. She holds a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts and an MBA from New York University. In addition, she teaches art history at Purchase College in New York.