This post is part of a blog series leading up to the American Musicological Society annual conference taking place in Vancouver, Canada from November 3–6. Please visit our booth if you are attending, and otherwise stay tuned for more content related to our Music books and journals programs.

by Tim Rutherford-Johnson, author of Music after the Fall: Modern Composition and Culture since 1989

Vancouver, unlike Paris, New York or Cologne, is unlikely to be high on anyone’s list of cities to have had an impact on the direction of contemporary art music. Yet when I was writing Music after the Fall, I was struck by how often my attention was drawn to the Canadian West Coast – and not only because of the frequently beautiful music that gets made around here. Thanks to the teaching of Christopher Butterfield and the Czech émigré Rudolf Komorous at the University of Victoria, just the other side of the Salish Sea, two generations of composers have emerged with distinctive voices. Among them are Martin Arnold, Cassandra Miller, and Linda Catlin Smith, whose 2007 piano solo Thought and Desire exemplifies an understated, highly personal style that is fascinatingly detached from the pressures of the US or European scenes.

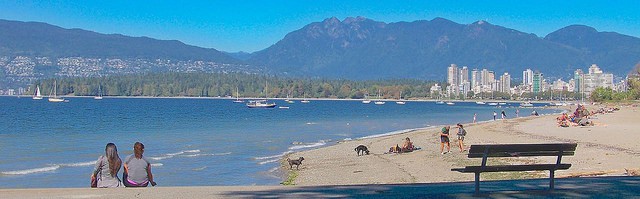

One of the very first composers featured in the book, Hildegard Westerkamp, has been based in Vancouver since 1968. My opening chapter even includes a photograph of Kitsilano Beach.

Westerkamp, and the beach, appear thanks to her Kits Beach Soundwalk, an electroacoustic piece that transforms recordings of waves and barnacles into a magic realist fantasy through 300 years of music history. Unlike the composers mentioned above, Westerkamp was taught by R. Murray Schafer at Simon Fraser University. An environmentalist as well as a musician, the 83-year-old Schafer can probably claim to be Canada’s most celebrated living composer. His reputation stands on his work as the father of “acoustic ecology,” the scientific and creative exploration of our sounding environment.

Together with a like-minded group of composers and students (Westerkamp joined them a little later), he set up in 1969 the World Soundscape Project to raise public awareness of environmental noise and sound, document the aural environment, and establish a practice and methodology for good soundscape design. The WSP produced a number of influential publications, among them field recordings made around Vancouver and Europe, and Schafer’s manifesto text The Tuning of the World, in which he sets out the field of soundscape studies alongside an ecological program for protecting the acoustic environment against man-made noise.

Field recording has gone on to become a significant artistic and scientific discipline, and the sounds of the environment have become commonplace within experimental music. Composers around the world today are capturing more and more exotic sounds – from beneath the surface of the Hudson River to the insides of bottles, pipes and manholes – and incorporating them into their music in a variety of ways. The appeal is not only environmental, but also about redefining the nature of musical subjectivity – ultimately, what it means to listen and to be part of a sounding world. Vancouver may be out of the way to some, but its reverberations endure.

Tim Rutherford-Johnson is a London-based music journalist and critic. He was the contemporary music editor at Grove Music Online and edited the most recent edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Music. He has taught at Goldsmiths College and Brunel University, and since 2003 he has written about new music for his blog, The Rambler.

Tim Rutherford-Johnson is a London-based music journalist and critic. He was the contemporary music editor at Grove Music Online and edited the most recent edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Music. He has taught at Goldsmiths College and Brunel University, and since 2003 he has written about new music for his blog, The Rambler.