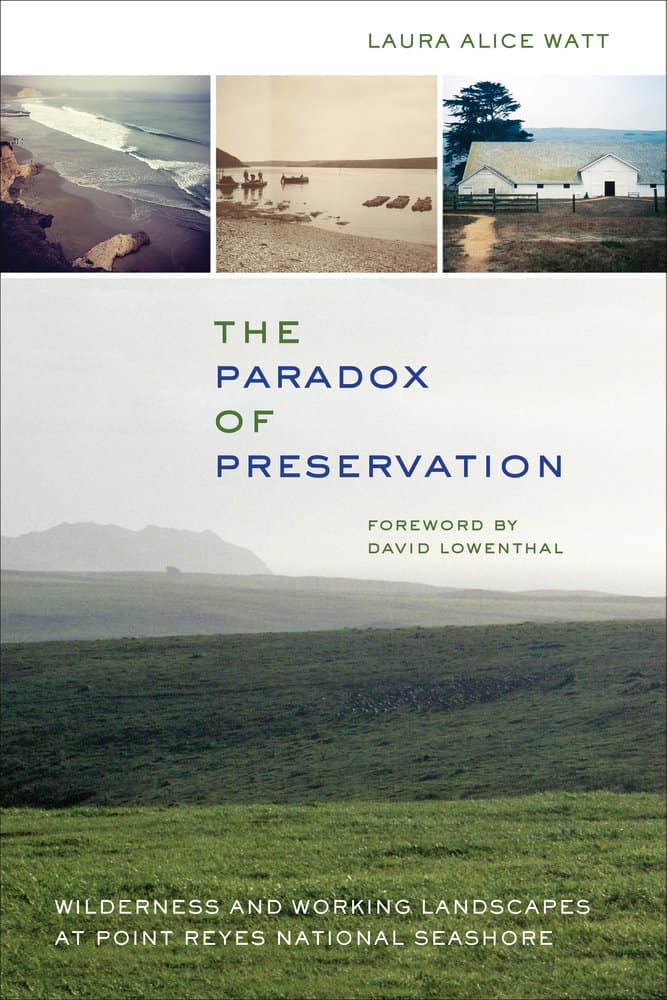

by Laura Alice Watt, author of The Paradox of Preservation: Wilderness and Working Landscapes at Point Reyes National Seashore

Today is the 54th anniversary of the establishment of the Point Reyes National Seashore, a much-beloved destination for people around the Bay Area and far beyond. Over the years I have been researching the peninsula’s landscape history, many people have asked, why are there still ranches in the park? Classic national parks like Yosemite or Yellowstone do not contain active agriculture, so indeed the presence of dairy cows and beef cattle adjacent to Point Reyes’ beaches must seem puzzling to some.

Yet these historic agricultural families have remained in place for a reason, as my forthcoming book The Paradox of Preservation explores in depth. For over a century before it became a national seashore, Point Reyes was famous for its agriculture. Starting in the 1850s, renowned dairy and beef ranches were established on privately-owned property across the peninsula. In the late 1950s, the area was first proposed as a Seashore, aimed at providing recreation opportunities close to the metropolitan Bay Area—but even in the earliest discussions, a key concern was the possible effects of establishing a park on the local agricultural economy. As early as 1958, in a letter to Senator Clair Engle (one of the initial sponsors of the legislation), then-president of Marin Conservation League Caroline Livermore wrote: “As true conservationists we want to preserve dairying in this area and will do what we can to promote the health of this industry which is so valuable to the economic and material well being of our people and which adds to the pastoral scene adjacent to the proposed recreation project.” Throughout two years of Congressional hearings, no one testified at any time in favor of shutting down existing ranching, dairying, or oystering operations. Instead, the 1962 legislation reflected a strong commitment to retaining and sustaining existing agricultural uses, as they served the public values that the new national seashore was created to protect.

Yet these historic agricultural families have remained in place for a reason, as my forthcoming book The Paradox of Preservation explores in depth. For over a century before it became a national seashore, Point Reyes was famous for its agriculture. Starting in the 1850s, renowned dairy and beef ranches were established on privately-owned property across the peninsula. In the late 1950s, the area was first proposed as a Seashore, aimed at providing recreation opportunities close to the metropolitan Bay Area—but even in the earliest discussions, a key concern was the possible effects of establishing a park on the local agricultural economy. As early as 1958, in a letter to Senator Clair Engle (one of the initial sponsors of the legislation), then-president of Marin Conservation League Caroline Livermore wrote: “As true conservationists we want to preserve dairying in this area and will do what we can to promote the health of this industry which is so valuable to the economic and material well being of our people and which adds to the pastoral scene adjacent to the proposed recreation project.” Throughout two years of Congressional hearings, no one testified at any time in favor of shutting down existing ranching, dairying, or oystering operations. Instead, the 1962 legislation reflected a strong commitment to retaining and sustaining existing agricultural uses, as they served the public values that the new national seashore was created to protect.

The continuing presence of cattle ranches on Point Reyes’ rolling grasslands offers a vision of how working landscapes—places characterized by “an intricate combination of cultivation and natural habitat,” shaped by the work and lives of many individuals over generations, maintaining a distinct character yet responding to the changing needs of its residents—should be recognized as part of both natural and cultural heritage worth protecting. The U.S. national park system contains areas that primarily aim to preserve natural scenery as well as those that primarily preserve history and cultural heritage; Point Reyes offers the suggestive possibility of protecting all types of heritage resources together, as a landscape whole and including the resident users’ input in management, rather than separately. I hope you will join me in celebrating the Seashore’s anniversary on the 13th, in hopes of many more years of public enjoyment of this unique and inspiring model of land protection and stewardship.