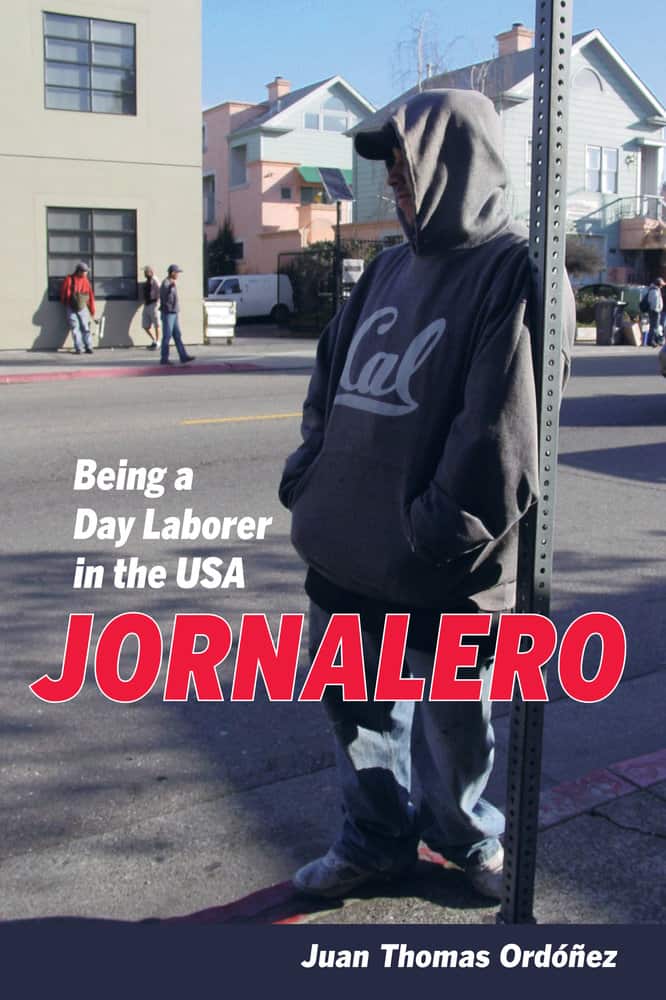

By Juan Thomas Ordonez, author of Jornalero: Being a Day Laborer in the USA

This guest post is published in advance of the American Sociological Association conference in Chicago.Check back every day for new posts through the end of the conference on Tuesday, August 25th.

In what ways would you say that the interplay of isolating factors affecting migrant workers damages their position in American society overall?

When I first came to the corner where I ended up working with day laborers, I initially saw a “group” of men who seemed to look out for each other. As time went by I realized they really did not know one another well and were more or less on their own in a state of isolation from family, friends and the state, which they avoided in all forms, real and imagined. By imagined I mean they avoided representatives of what they thought was the state or places where the state had influence. These included the police, hospitals and even immigrant rights NGOs for some people. Men were afraid to give out their name and address to people they did not trust and made very radical decisions like moving or not going to work based on hearsay and rumor. Clearly this is not a good position for anyone in any society, as it raises risk of injury and discrimination at work (employers know the day laborers will not seek legal help that is effective), distrust of institutions that aim to protect all members of a community, and ultimately, it results in a form of belonging “in the shadows” which goes against the most basic and cherished premises the United States prides itself on.

Do you believe that any recent developments have, or have the potential to, change la situación as you knew it while writing Jornalero?

The short answer is no. There was much optimism a few years after I left because California and other states decided to allow undocumented migrants to have a driver’s license or something of the sort, which in theory would facilitate many  aspects of life that were very difficult or confusing. Think of all the things you do with your driver’s license besides driving; every time you have used it to get on an airplane, at the bank, or even to enter buildings with high security. The list can get even longer when you think about purchasing things where your ID is required which at the time of fieldwork included cellphones. But the truth is such policies simply redraw the boundaries of migrant illegality and reshape the incompletes belonging. I don’t see how migrants are any closer to social inclusion and, more importantly, to the recognition of their contributions to US society and of their everyday suffering. If anything, with the upcoming elections we can see undocumented migration is again at the heart of the political debate and many proposals propose situations that are even more drastic than the one the men I studied were going through at the height of the 2008 economic crisis.

aspects of life that were very difficult or confusing. Think of all the things you do with your driver’s license besides driving; every time you have used it to get on an airplane, at the bank, or even to enter buildings with high security. The list can get even longer when you think about purchasing things where your ID is required which at the time of fieldwork included cellphones. But the truth is such policies simply redraw the boundaries of migrant illegality and reshape the incompletes belonging. I don’t see how migrants are any closer to social inclusion and, more importantly, to the recognition of their contributions to US society and of their everyday suffering. If anything, with the upcoming elections we can see undocumented migration is again at the heart of the political debate and many proposals propose situations that are even more drastic than the one the men I studied were going through at the height of the 2008 economic crisis.

What key points do you wish for readers to take with them after reading your book?

I think the most important point I would like readers to take from reading my book is that living “undocumented” lives in the United States is harsh and full of sacrifice. The men in Jornalero loved joking about their suffering (and everything else in their lives) but in between lines were terrible experiences of separation, discrimination, and sorrow that are direct results of their contribution to the communities where they live and work. The people whose houses they painted, whose furniture they moved, all the gardens they fixed up, and everything else are all tied up in the system. Migrants are not in the U.S for an easy life and most have to face conditions both at work, on the corner, and in the places they live that most people in the country would not recognize. These conditions, in fact, are what makes their labor an essential part of the labor market; that is cheap and disposable workers with little access to any form of social protection. I think it is also important to recognize that even in migrant tolerant areas like the Bay Area there is a fair share of employer abuse and discrimination that goes unseen and is not talked about.

Juan Thomas Ordóñez has a PhD in medical anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, and is Professor of Anthropology at the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, Colombia.