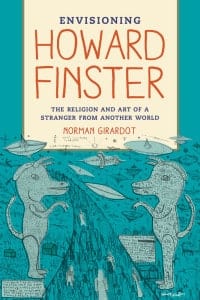

By Norman Girardot, author of Envisioning Howard Finster: The Religion and Art of a Stranger from Another World

Norman Girardot, fresh from attending the “America is Hard to See” exhibit at the (New) Whitney Museum of American Art, reflects on the collection’s missed opportunities and what he perceives as token efforts to curate outsider art in relation to mainstream tradition. He also notes that the outsider artist Howard Finster, the so-called “backwoods William Blake” and the “Southern Andy Warhol,” should be taken seriously as a maverick visionary and quasi-pop artist.

Having just toured the new Whitney museum of American art which brazenly juts out into the Hudson like an ocean liner steaming forth from the highline docks of Chelsea, I am happy to report that the architect Renzo Piano has designed another wonderfully engaging and functional building for appreciating art. The inaugural exhibition “America is Hard to See” (May 1–September 27, 2015) is Impressive and enlightening especially for the mostly adept historical selection, thematic contextualization, and provocative juxtaposition of works in the large permanent Whitney collection (covering the years from the 1920s onward). American art is certainly difficult to see in its motley, unruly, and ever-changing splendor and the Whitney has laid it out quite brilliantly and at times hauntingly. There even was an attempt finally to bring so-called self-taught or outsider art into the larger fabric of American art history – witness on the seventh floor the evocative juxtaposition of a terse yet spritely Bill Traylor drawing (Walking Man, 1930) with a provocative Marsden Hartley portrait on one side and a more florid Thomas Hart Benton painting on the other side. Each is terrific when viewed singularly, but when seen together the real eclectic vibrancy of American art shines forth. For me this seemed to signal additional brave insider/outsider juxtapositions to come on that floor and below – for example, pairings with Calder’s glorious found object and makeshift “Circus” or Joseph Cornell’s mysterious boxed worlds. Alas that was not to be and despite the blurred exhibition of insider and outsider art promoted by the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni at the New Museum and at the 2013 Biennale (and as seen on a smaller scale at various NYC galleries like Christian Berst), the Whitney made at best only a token effort in this direction. The missed opportunities were everywhere, but I am not trying to suggest that incorporations of non-mainstream or unschooled art needed to be everywhere in the show. The curators might simply say that they were, after all, working only with what was available in the permanent collection and the fact is that for all sorts of (not always legitimate but nevertheless historically understandable) reasons that kind of art was not collected.

This situation was noted in a review of the new Whitney by Ingrid Rowland in the New York Review of Books (June 25, 2015) who regretted the almost complete absence of any kind of early 20th century self-taught “primitives” or folk art (keeping in mind the Bill Traylor exception which Rowland seems to have missed). Rowland in fact suggests one plausible explanation for the Whitney’s truncated perspective on the history of American art – namely “because a collection that began as the whim of a wealthy amateur sculptor [Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney] will not easily lose its connection with her world, in all its various aspects, hidebound and libertine. The Whitney collection retains, inevitably, its connections with money and the makers of money.” No doubt it’s not that simple, but she’s got a point. Reflecting on the Whitney’s penchant for pungent and revealing juxtapositions, Rowland goes on to say that “if Andrew Wyeth can be lined up with Man Ray, why not put John Steuart Curry’s ‘Baptism in Kansas’ next to an apocalyptic vision by crazy man Howard Finster”? Why indeed, although I must say that it’s unfortunate that in many art circles (particularly in New York) it’s still taken as a secular gospel truth that Finster as a Southern evangelical Christian must have been some kind of crazy fundamentalist nut. This is not the forum to argue otherwise, but I must point out that Finster was only crazy like a crafty fox or cheetah and was certainly not a conventional fundamentalist. The truth about Finster is much stranger and interesting with reference to both his visionary religion and his “bad and nasty” art. In other words, Finster really should be taken seriously as a maverick visionary Christian and as an innovatively creative American artist. It may be remembered that Finster was often called, mostly with tongue-firmly-in-cheek, the “backwoods William Blake” (a non-conformist visionary Christian who was influenced by Swedenborgianism the way Finster was influenced by UFO contactees) and the “Southern Andy Warhol” (a creatively enterprising signage artist of cultural detritus who, like Finster, saw art as an “amazing” pop advertising medium). The truth is that these descriptive phrases are actually much more accurate than we ever imagined.

Norman Girardot is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of religion at Lehigh University.